More than 80 domestic cats have been diagnosed with bird flu since 2022, raising concerns about the virus’s spread and potential public health implications. This article delves into the current situation, what it means for House Cats, and how to protect your feline companions.

Since 2022, over 80 domestic cats, alongside various other mammal species, have tested positive for bird flu. These cases primarily involved barn cats residing on dairy farms, feral cats, and pets with outdoor access, who likely contracted the virus through hunting infected rodents or wild birds. However, a worrying trend is emerging: house cats are increasingly becoming infected with the H5N1 strain of bird flu, currently driving the U.S. outbreak. These infections have been linked to the consumption of raw food or unpasteurized milk, with some cases proving fatal for these beloved pets.

While the current bird flu strain has not evolved to easily spread among humans, and no cat-to-human transmission has been reported during this H5N1 outbreak, the inherent risk of cats carrying diseases home remains. Cats, often described as semi-domesticated, have the potential to bring infections from their outdoor explorations into our homes.

“Companion animals, especially house cats, represent a public health risk regarding zoonotic transmission to humans,” states virologist Angela Rasmussen from the University of Saskatchewan’s Vaccine and Infectious Disease Organization. Our close interactions with cats, including cuddling and sharing living spaces, highlight this concern. Cats’ habits, such as drinking from our glasses and walking on kitchen counters, further emphasize the need for awareness. “Reducing the risk to your cats is directly reducing the risk to yourself,” Rasmussen advises, stressing the importance of preventative measures for both pet and public health.

While Rasmussen believes fear is unwarranted, she advocates for proactive precautions. Recognizing bird flu symptoms in house cats is crucial. According to Michael Q. Bailey, president-elect of the American Veterinary Medical Association, signs include nasal discharge and eye secretions. H5N1 can also manifest neurological issues like disorientation and seizures, symptoms that overlap with rabies. Given rabies’ severity and fatality, any suspected animal must be euthanized. Bailey urges pet owners to ensure their cats are current on rabies vaccinations and other essential preventative care.

House cat drinking milk from a bowl, illustrating a potential risk factor for bird flu infection in domestic cats.

House cat drinking milk from a bowl, illustrating a potential risk factor for bird flu infection in domestic cats.

Veterinarian Jane Sykes, an infectious disease specialist at the University of California-Davis School of Veterinary Medicine, advises against immediately assuming bird flu if a house cat becomes ill. Upper respiratory infections are common in cats, while H5N1 remains relatively uncommon. Sykes, who feeds her indoor cat, Freckles, exclusively commercial kibble, expresses no concern about H5N1, as the processing of dry and canned pet food eliminates viruses.

The Growing Concern: More Cat Cases, Increased Human Risk

The practice of feeding pets raw meat or unpasteurized milk, driven by beliefs in more nutritious or natural diets, is now under scrutiny. The American Veterinary Medical Association cautions against raw diets due to foodborne pathogens like salmonella and listeria, and now, the highly pathogenic H5N1 virus.

Veterinarians play a vital role in safeguarding human health from zoonotic diseases by maintaining pet health. The American Veterinary Medical Association emphasizes that while the risk of H5N1 transmission from pets to humans is “considered extremely low, but not zero,” vigilance is necessary.

Public health agencies, including those in Los Angeles County and Washington state, have issued warnings against raw food diets for pets, highlighting human health concerns. The FDA’s recent mandate requiring pet food manufacturers to update safety plans to address bird flu further underscores this growing worry.

This action followed the discovery of H5N1 in an indoor cat in Oregon that died after consuming a recalled frozen turkey product from Northwest Naturals. Testing confirmed a genetic match between the virus in the raw pet food and the infected house cat. Northwest Naturals initiated a voluntary recall of the affected batch, though they have voiced concerns about the accuracy of the Oregon Department of Agriculture’s testing.

In another instance, Los Angeles County reported five house cats from two households testing positive for bird flu after consuming unpasteurized raw milk from Raw Farm dairy. Raw Farm subsequently recalled its milk and cream products after H5N1 was detected, but they dispute any food safety issues, framing the concern as “a political issue.”

Veterinarians also advise against allowing house cats unsupervised outdoor access due to the risk of H5N1 exposure from potentially infected animals. Bruce Kornreich, director of Cornell University’s Feline Health Center, emphasizes the broad host range of this “very scary virus.”

A 2016 incident documented a cat infecting a veterinarian with bird flu (H7N2 strain) in New York City. The vet experienced mild symptoms and recovered, demonstrating that cat-to-human transmission, while rare, is possible. While H7N2 differs from the current H5N1 strain, Jane Sykes points out this event confirms the theoretical possibility of avian influenza transmission from cats to humans.

Research on bird flu transmission from companion animals to humans is limited, but Angela Rasmussen agrees it’s a valid concern. Increased animal infections elevate the potential for human transmission. Most human H5N1 cases have occurred in agricultural workers with direct poultry or cattle contact. Of the confirmed human cases in the U.S., one fatality occurred in an immunocompromised individual with bird contact.

Zoonotic disease experts advocate for enhanced H5N1 surveillance in all companion animals. Even with a low human fatality rate, H5N1 remains a public health threat.

Mutation Potential and Ongoing Surveillance

A significant concern with the H5N1 outbreak is the virus’s ability to mutate. Minor genetic changes could enable human-to-human transmission. Suresh Kuchipudi, a virologist at the University of Pittsburgh School of Public Health, emphasizes that increased human infections raise the likelihood of adaptation for efficient human transmission. Kuchipudi’s research includes studying H5N1 in house cats.

Another worry is reassortment, where co-infection with two viruses allows genetic material exchange, creating novel viruses. Influenza viruses are prone to reassortment, prompting virologists to monitor for cases leading to more contagious and virulent strains.

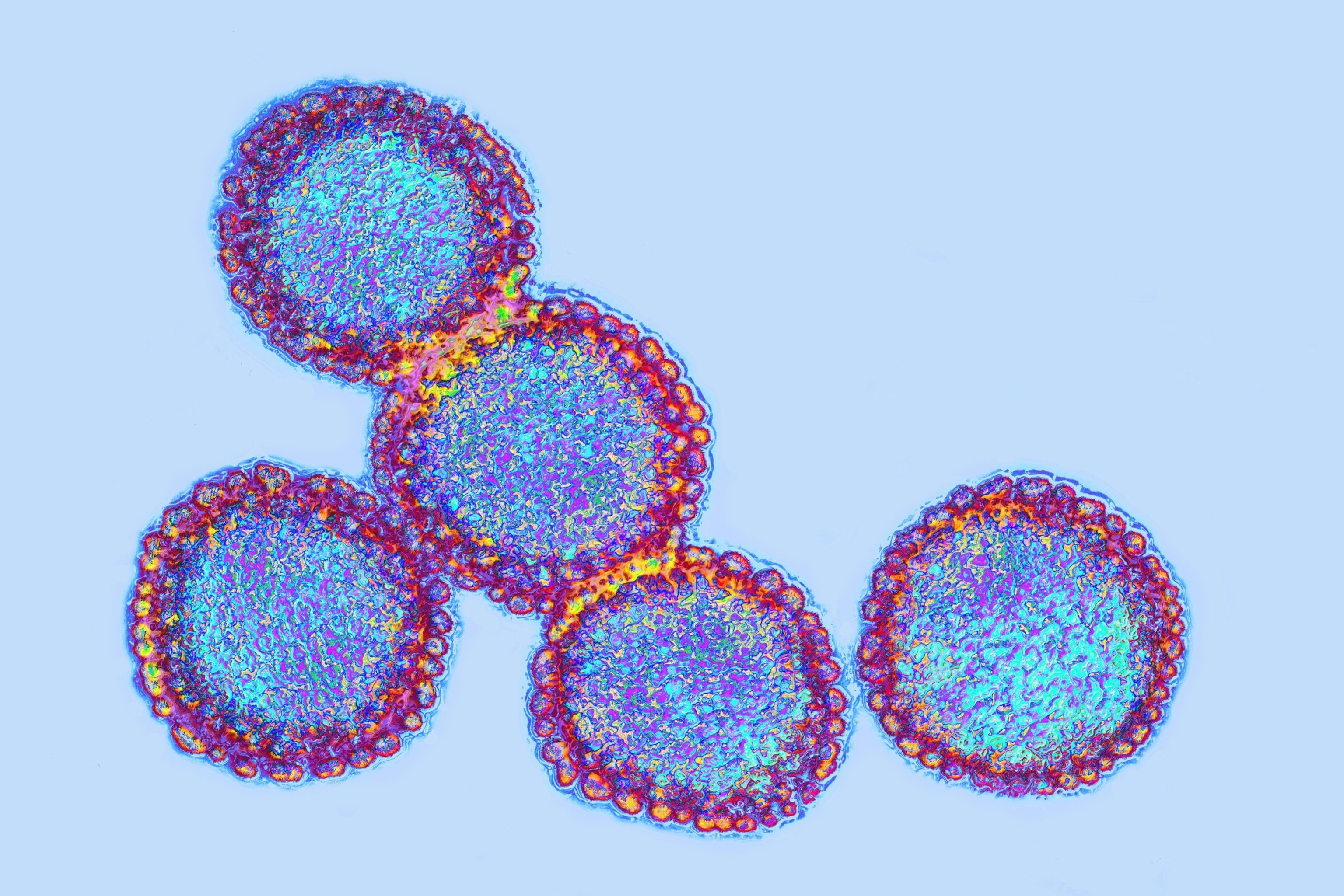

Microscopic view of avian influenza virus, highlighting the ongoing concern of bird flu transmission and mutation.

Microscopic view of avian influenza virus, highlighting the ongoing concern of bird flu transmission and mutation.

Virologist Rasmussen expresses greater concern about reassortment in pigs, as their respiratory physiology is more similar to humans than cats. While H5N1 hasn’t yet reached commercial hog operations, Rasmussen hopes it remains contained. Kuchipudi notes reassortments are infrequent but unpredictable. While some outcomes are benign, the 1918 flu pandemic, causing an estimated 50 million deaths, likely originated from avian virus reassortment. Global influenza surveillance networks are crucial for pandemic preparedness and prevention.

Winter, with its increased influenza virus circulation, is considered “reassortment season,” according to Rasmussen. While reassortment in house cats is theoretically possible, especially given their susceptibility to seasonal flu, it’s highly unlikely. Rasmussen suggests a more probable scenario is a house cat transmitting H5N1 to a human with seasonal flu, leading to reassortment in the human. However, she considers this risk low, depending on the cat’s viral shedding and human exposure levels. “Unless the cat is really shedding a ton of virus, and you’re kind of making out with the cat, I think it would be hard,” she jokes.

Both Rasmussen and Kuchipudi emphasize the need for more research to understand viral shedding in cats and transmission routes. A CDC study on H5N1 in cats was delayed, but emails obtained by KFF Health News suggest house cats likely contracted bird flu from dairy workers. Kuchipudi urges re-evaluating assumptions about bird flu, noting the unforeseen infection of dairy cattle in the current outbreak.

Dogs and Bird Flu: A Different Picture

The FDA confirms that other domestic animals, including dogs, can contract bird flu. While no confirmed H5N1 cases exist in U.S. dogs, infections have been reported and proven fatal in dogs in other countries.

There’s ongoing debate and limited research on whether feline biology makes house cats more susceptible to H5N1 than other mammals. However, cat behaviors, including dairy consumption and hunting wild birds, increase their risk. The prevalence of feral cat colonies compared to stray dog packs may also contribute.

Controlling H5N1 in wild birds is largely impossible, as Rasmussen explains, “It’s flying around in the skies. It’s migrating north and south with the seasons.” However, significant steps can be taken to protect house cats and minimize risk. These include avoiding raw food and unpasteurized milk, and limiting interaction with rodents and wild birds.

This article is part of a collaboration between NPR and KFF Health News.