For anyone unfamiliar with the intricacies of feline reproduction, the question “How Often Do Cats Go In Heat?” is a crucial one, especially for owners of unspayed female cats, known as queens. Unlike dogs or humans, cats have a unique estrous cycle that can be both fascinating and, at times, challenging to manage. Understanding this cycle is paramount for responsible cat ownership, whether you’re a seasoned cat lover or a first-time pet parent.

Decoding the Cat Heat Cycle: Age of Onset

The age at which a cat first experiences heat can vary, but generally, most queens will begin their estrous cycle between 5 to 9 months old. However, it’s not uncommon for some kittens to start as early as 3 to 4 months, while others might not cycle until they are closer to 18 months. Several factors influence this timeline, including:

- Breed: Certain breeds might mature slightly earlier or later than others.

- Weight: A cat’s overall health and body condition play a role in hormonal development.

- Time of Year: As cats are seasonally polyestrous, meaning their cycles are influenced by daylight hours, the time of year significantly impacts when they first cycle. Cats born in spring may cycle earlier than those born in autumn.

Duration and Stages of the Feline Heat Cycle

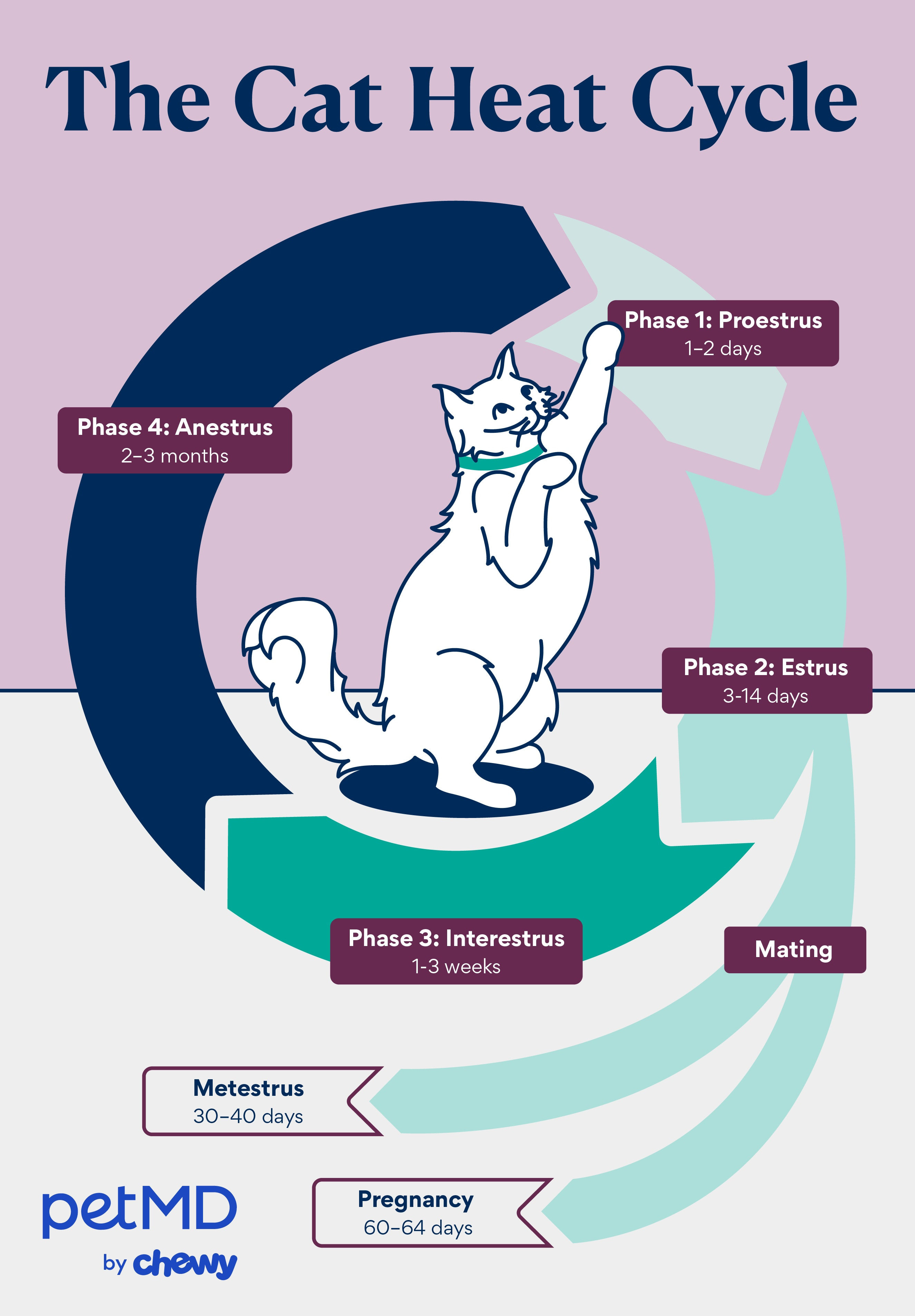

The cat heat cycle isn’t a continuous state but rather a series of distinct stages. Understanding these stages is key to recognizing your cat’s behavior and needs.

Illustration depicting a cat in the heat cycle

Illustration depicting a cat in the heat cycle

Proestrus: The Prelude to Heat

Proestrus is the initial phase, marking the beginning of the heat cycle. During this stage, estrogen levels begin to rise. Typically lasting just 1 to 2 days, proestrus is often subtle, with no outwardly visible symptoms noticeable to most owners. You might observe male cats showing increased interest in your female cat, but she will not be receptive to mating at this point.

Estrus: The “In Heat” Phase

Estrus is what most people recognize as a cat being “in heat.” This is the most prominent phase of the cycle, typically lasting around one week, but it can range from 3 to 14 days. During estrus, a queen displays marked behavioral changes driven by hormonal fluctuations and the instinct to mate.

Common signs of a cat in estrus include:

- Increased Affection: She may become excessively affectionate, rubbing against furniture, legs, and demanding attention.

- Excessive Vocalization: Queens in heat are known for their loud, distinctive calls, often described as yowling or caterwauling. This vocalization is intended to attract male cats.

- Restlessness: She might appear agitated, pacing, and unable to settle down.

- Posturing: A characteristic behavior is the “heat crouch” – the queen lowers her front body, raises her hindquarters, treads with her back legs, and deflects her tail to the side, signaling receptivity to mating.

It’s crucial to understand that estrus is the stage where mating occurs.

Interestrus and Metestrus: Intervals Between Heats

Cats are induced ovulators. This biological term signifies that a queen’s ovaries will only release eggs if she mates with a male cat. This unique reproductive mechanism leads to two potential post-estrus phases:

- Metestrus (Post-Ovulation): If mating occurs during estrus, ovulation is triggered, and the cycle enters metestrus. Whether or not fertilization occurs, metestrus lasts for 30 to 40 days. If pregnancy results, this phase transitions into gestation, lasting approximately 60 to 64 days. If no pregnancy occurs, the cycle will eventually return to proestrus.

- Interestrus (Non-Ovulation): If a queen in estrus does not mate, ovulation does not occur. Instead of metestrus, she enters interestrus, a period of 1 to 3 weeks where in-heat behaviors subside. Following interestrus, the cycle will restart with proestrus, and the queen will go into heat again. This can lead to closely spaced heat cycles if mating does not happen.

Anestrus: The Resting Phase

Anestrus is a period of reproductive inactivity. Cats are seasonal breeders, and anestrus typically occurs during the shorter daylight months of the year, usually 2 to 3 months in winter. During anestrus, there is minimal hormonal activity, and the queen does not cycle. As daylight hours increase in late winter and early spring, cats transition out of anestrus and begin cycling again.

Seasonal Influence on Heat Cycles: How Often is “Often”?

The answer to “how often do cats go in heat?” is heavily influenced by the seasons. Cats are long-day breeders, meaning their reproductive cycles are stimulated by increasing daylight hours.

- Peak Season: Heat cycles are most frequent during spring and summer, typically starting in late winter or early spring (February/March in the Northern Hemisphere) and peaking from February to April.

- Extended Breeding Season: Cycles can continue throughout the longer daylight months, often lasting until October or November.

- Geographic Variation: Cats in regions with consistently warm climates and longer daylight hours throughout the year may cycle more frequently and even year-round compared to cats in areas with distinct seasons.

- Indoor vs. Outdoor Cats: Artificial indoor lighting can sometimes influence a cat’s cycle, potentially leading to more frequent cycling even in winter months, compared to outdoor cats whose cycles are more strictly tied to natural daylight.

Therefore, during the breeding season, a queen may experience heat cycles every 2 to 3 weeks if she doesn’t mate and ovulate. This can mean multiple heat cycles within a single breeding season.

Recognizing the Signs: Is Your Cat in Heat?

Unlike dogs, cats do not typically bleed during their heat cycle. Therefore, recognizing the behavioral signs is crucial. As mentioned earlier, key indicators that your cat is in heat include:

- Excessive Affection and Attention-Seeking: More clingy than usual, constantly wanting to be petted.

- Vocalization: Loud meowing, yowling, or caterwauling.

- Restlessness and Agitation: Pacing, inability to settle.

- Posturing: The heat crouch position.

- Decreased Appetite: Some cats may eat less during heat.

- Urine Marking (Less Common): In some cases, cats in heat might urinate more frequently or outside the litter box, though this is less typical than in male cats marking territory.

It’s understandable for pet owners to be concerned when witnessing these dramatic behavioral changes, sometimes mistaking them for signs of pain. If you are unsure or worried about your cat’s behavior, consult with your veterinarian to rule out any underlying medical issues.

Managing a Cat in Heat: What to Do

If you don’t intend to breed your cat, the most important step is to prevent unwanted pregnancies.

- Keep Her Indoors: During heat, queens should be strictly kept indoors to prevent mating with stray or outdoor male cats.

- No Lifestyle Changes Needed (Generally): Otherwise, there are no specific necessary lifestyle changes for a cat in heat, beyond managing the behavioral symptoms. Provide extra attention and comfort if your cat is restless.

However, it’s vital to monitor the frequency and duration of heat cycles. Prolonged or abnormal cycles can sometimes indicate underlying issues like:

- Pseudopregnancy (False Pregnancy): Hormonal imbalances can sometimes cause a cat to exhibit signs of pregnancy after heat without being pregnant.

- Mucometra: Accumulation of mucus in the uterus.

- Pyometra: A serious and life-threatening uterine infection. Pyometra is more common in older, unspayed cats and can occur after heat cycles.

Seek immediate veterinary attention if your cat exhibits any of the following signs during or after a heat cycle:

- Lethargy or weakness

- Loss of appetite

- Fever

- Vaginal discharge (especially if it is bloody or foul-smelling)

- Excessive drinking or urination

- Swollen abdomen

Preventing Heat Cycles: Spaying is Key

The only definitive way to prevent heat cycles and unwanted pregnancies in female cats is spaying (ovariohysterectomy).

- No Good Reason to Leave Cats Intact (Unless Breeding): Unless you are a responsible breeder participating in a recognized breeding program, there are no health benefits to allowing your cat to go through heat cycles.

- Health Risks of Not Spaying: Unspayed cats are at significantly higher risk of developing pyometra, pseudopregnancy, mammary cancer, and ovarian cancer.

- Recommended Spaying Age: Veterinarians typically recommend spaying kittens at 5 to 6 months of age, ideally before their first heat cycle to prevent it entirely. Spaying is a routine and safe procedure when performed by a qualified veterinarian.

FAQs About Cats in Heat

Do cats bleed when in heat?

No, cats should not bleed during a normal heat cycle. Bloody vaginal discharge is abnormal and requires immediate veterinary attention as it could indicate a serious problem. A clear vaginal discharge is sometimes observed during proestrus, but blood is not normal.

Can you spay a cat in heat?

Yes, spaying a cat in heat is possible and safe. While some veterinarians might prefer to spay a cat not in heat if it’s a routine spay, it’s often necessary and safe to spay a queen mid-cycle, especially in rescue situations or to prevent further heat cycles and potential pregnancy. Delaying spaying to wait for anestrus can increase the risk of pregnancy and prolong the stress of heat for the cat.

Do male cats go into heat?

No, male cats do not experience heat cycles. Heat is a phenomenon related to the female estrous cycle and ovulation. However, intact male cats (toms) are always reproductively ready and can mate with females at any time when a queen is in heat.

How many days does a cat stay in heat?

The “in heat” phase (estrus) typically lasts for 3 to 14 days, with an average duration of about one week.

How can I tell if my cat is in heat?

Observe your cat for the typical behavioral changes: vocalization, increased affection, restlessness, and the heat crouch posture. If you suspect your cat is in heat, consult your veterinarian for confirmation and guidance, especially if you are unsure or concerned about your cat’s behavior.

By understanding the feline estrous cycle and recognizing the signs of heat, cat owners can provide the best care for their queens, prevent unwanted pregnancies, and make informed decisions about spaying to protect their cat’s long-term health and well-being.