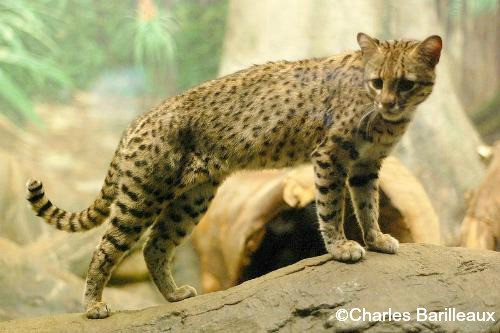

The Geoffroy’s cat (Leopardus geoffroyi) stands out as one of the most adaptable and widely distributed wild cat species throughout South America. From the vibrant ochre hues in its northern territories to the silver-grey coats in the southern regions, and the diverse shades in between, the Geoffroy’s cat displays remarkable coat variation. A defining feature is its striking pattern of numerous small, round, black spots, uniformly sized and spaced, creating a distinctive ‘necklace’ across its chest. Adding to its unique markings are several black stripes adorning its crown and two on each cheek. The underparts are lighter in color, also adorned with solid spots, completing the Geoffroy’s cat’s visually arresting appearance.

Geoffroy's cat exhibiting its distinctive spotted coat pattern and robust build, a small wild cat native to South America.

Geoffroy's cat exhibiting its distinctive spotted coat pattern and robust build, a small wild cat native to South America.

Physical Characteristics and Size

Geoffroy’s cats are characterized by fairly sturdy legs, marked with bands on the upper portions where the spots extend down to their toes. Their tails, tipped with black and approximately half the length of their head and body combined, are encircled by several black rings. The cats possess large, rounded ears, black on the exterior and marked with distinctive white central spots. Their eyes exhibit irises that range in color from a deep golden hue to a greenish-grey.

Beyond the commonly spotted coat, a melanistic variation also exists, more frequently observed in forested and wetland habitats. Four recognized subspecies display considerable differences in coat color and size. The largest Geoffroy’s cats are found in the southern parts of their distribution range, distinguished by longer and paler fur. Moving northwards into Paraguay, these cats tend to be smaller and exhibit darker coats. Specimens from northern Argentina were once misclassified as a separate species due to their less defined spotting, earning them the name ‘salt desert cats’. In certain areas, distinguishing Geoffroy’s cats from closely related species like the Kodkod (Leopardus guigna) and the Pampas cat (Leopardus colocolo) can present identification challenges.

Distribution Across South America

Geographical distribution range map of the Geoffroy's cat (*Leopardus geoffroyi*) in South America, highlighting its widespread presence across multiple countries.

Geographical distribution range map of the Geoffroy's cat (*Leopardus geoffroyi*) in South America, highlighting its widespread presence across multiple countries.

The Geoffroy’s cat’s distribution spans a significant portion of South America, inhabiting regions within the Andes of southern Bolivia, southern Brazil, Paraguay, Argentina, Uruguay, and southern Chile. Notably, they have been documented at elevations reaching up to 3,800 meters in the Bolivian Andes, showcasing their adaptability to varying altitudes.

In southern Brazil, at the northernmost edge of their range, Geoffroy’s cat populations overlap with those of the Southern Tiger cat (Leopardus guttulus). These two species share similarities in body proportions and general appearance, leading to instances of hybridization observed by researchers, indicating a close genetic relationship and ecological overlap.

Geoffroy’s cats are known for their dispersal capabilities, having been recorded to travel distances exceeding 100 km. Studies in the wet pampas grasslands of Argentina have revealed home range sizes averaging between 2.5 to 12 square kilometers, with male territories typically 25% larger than those of females. In contrast, home ranges in Torres del Paine National Park in Chile were found to be somewhat larger, ranging from 7 to 10 square kilometers. While female home ranges may overlap, male territories generally do not, and males consistently exhibit larger home ranges compared to females, a common trait in many felid species reflecting resource and mate acquisition strategies.

Population density in Argentina has shown considerable fluctuation. During drought periods, densities ranged from 2 to 36 cats per 100 square kilometers, but rebounded to a much higher density of 139 cats per 100 square kilometers just two years later, demonstrating a rapid population response to environmental changes and resource availability. In the Bolivian Chaco region, densities ranged from 2 to 42 cats per 100 square kilometers, highlighting regional variations in population distribution influenced by habitat quality and prey abundance.

Habitat Versatility

The Geoffroy’s cat exhibits remarkable habitat adaptability, thriving in a diverse array of environments, although it shows a preference for areas characterized by dense vegetation cover. A significant portion of its range is classified as arid or semi-arid, indicating its tolerance to drier conditions. Its habitat spectrum includes pampas grasslands, marsh grasslands, broad-leafed forests, savannas, dry shrublands, arid woodlands, and semi-desert and arid steppe uplands. This adaptability extends to both pristine and disturbed areas, and they can even be found in highly-degraded human-developed landscapes, showcasing their resilience in the face of habitat modification.

However, the presence of larger predators can influence their habitat use. As a generalist carnivore and the largest and most adaptable of the small cat species in tropical America, the Ocelot (Leopardus pardalis) can exert competitive dominance over other smaller cat species. In areas where Ocelots are present, species like the Geoffroy’s cat tend to avoid them due to the potential threat of predation. This ecological interaction, where a larger predator negatively impacts the distribution and behavior of smaller competitors, is known as the “ocelot effect”. When Ocelots inhabit protected areas, smaller cats may be forced into adjacent unprotected zones, increasing their vulnerability to habitat loss and human-related threats.

Ecology and Behavior

Geoffroy’s cats are primarily terrestrial animals, spending the majority of their time on the ground. Despite this, they are adept climbers and frequently utilize trees, demonstrating arboreal agility. They are also proficient swimmers, earning them the local nickname ‘fishing cats’ in some regions, with anecdotal evidence suggesting they readily enter water. In Chile, one documented female was observed crossing a 30-meter wide, fast-flowing river at least 20 times, highlighting their swimming capabilities. However, the more common local name, ‘gato de montes’, meaning ‘cat of the mountains’, reflects their broader habitat association.

Described as opportunistic predators, Geoffroy’s cats exhibit a flexible diet, feeding on the most readily available prey. They primarily hunt on the ground, but may also forage in water for frogs and fish, showcasing dietary adaptability. In southern Chile, studies revealed that the introduced European hare constituted over 50% of the diet in examined feces, and a cat was even observed carrying a large hare carcass into the trees, suggesting opportunistic predation on larger introduced species.

Conversely, a study in Argentina highlighted rodents as the primary dietary component throughout the year, with birds becoming more significant in spring and summer months. The European hare played a less prominent role in their diet in this region, indicating geographic variations in prey selection based on local availability.

This Argentinian study also indicated the importance of forest fragments for faecal and scent-marking behavior, while grasslands and marshes were primarily used for hunting and resting, suggesting a mosaic habitat utilization strategy. Geoffroy’s cats are predominantly nocturnal, with peak activity levels occurring in the middle of the night, aligning with the activity patterns of many of their prey species. The studied cats utilized both natural habitats and modified farmland, but exhibited a preference for areas with dense, high cover, emphasizing the importance of vegetation for shelter and hunting success.

Comparative research has shown that in habitats altered by cattle grazing and ranching, Geoffroy’s cats display increased activity levels, travel greater distances, and possess larger home ranges compared to those in protected areas. This behavioral shift likely reflects a reduced abundance of prey species in modified landscapes compared to protected areas with more natural vegetation. Larger home ranges may also indicate lower population densities in these altered environments.

Geoffroy’s cats in both study areas exhibited reduced activity levels during winter, a period when hares became a more important food source. Hares, being significantly larger than their typical prey, provide a substantial energy intake, potentially reducing the frequency of hunting required during colder months.

Cats in modified areas also displayed crepuscular activity, being active at dawn and dusk, in addition to nocturnal behavior. Resting sites included trees, small patches of tall grass, vizcacha burrows, and even unconventional locations like a car tire in a garbage pile, demonstrating adaptability in shelter selection. Nocturnal sightings revealed Geoffroy’s cats rapidly traversing agricultural fields, utilizing semi-natural grassland patches near streams, and moving along railroads and small patches of introduced trees adjacent to lakes. Five distinct sites were identified as repeated defecation locations, all associated with trees, either within the roots or among large fallen branches, suggesting territorial marking behavior.

Geoffroy’s cats are occasionally preyed upon by pumas. In areas where their habitats overlap, the smaller Geoffroy’s cat tends to shift towards more open landscapes, likely a predator avoidance strategy to minimize encounters with the larger puma.

Reproduction and Life Cycle

The gestation period for Geoffroy’s cats is approximately 72 to 78 days, resulting in litters of one to four kittens, typically born between December and May. Dens are established in well-protected locations such as rock crevices or dense shrubbery. Newborn kittens weigh between 60 to 100 grams. Weaning occurs around eight to ten weeks of age. Females reach sexual maturity at approximately 18 months, while males mature slightly later, around 24 months. Compared to domestic cats, young Geoffroy’s cats exhibit a slower developmental rate. Their lifespan can extend up to 18 years in the wild.

Threats to Survival

Geoffroy’s cats face a range of threats that impact their populations:

- Predation by domestic dogs: Uncontrolled domestic dogs pose a significant threat through direct predation.

- Vehicle collisions: Road mortality due to vehicle collisions is an increasing concern, especially in fragmented landscapes.

- Retaliation killing for poultry predation: Perceived or actual predation on poultry can lead to retaliatory killings by humans.

- Habitat loss and fragmentation: Deforestation and habitat conversion for agriculture and development are major drivers of habitat loss and fragmentation.

- Hunting for meat: In some areas, Geoffroy’s cats are hunted for their meat, although this is not believed to be a widespread major threat currently.

- Illegal capture for hybridization: They are illegally captured and bred with domestic cats to produce hybrid pets, a practice that can threaten wild populations and introduce genetic risks.

- Exposure to domestic carnivore diseases: Contact with domestic carnivores increases the risk of exposure to diseases prevalent in domestic animal populations.

Conservation Status and Efforts

The Geoffroy’s cat is currently classified as Least Concern by the IUCN Red List, reflecting its relatively wide distribution and adaptable nature. It is legally fully protected across its entire range, with hunting and trade prohibited in Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Paraguay, and Uruguay.

Despite being considered relatively common, the actual status of Geoffroy’s cat populations is not thoroughly understood, and the true impact of various threats remains difficult to accurately assess. Therefore, further research is crucial to better understand the species’ tolerance and resilience to habitat changes and anthropogenic pressures. Key conservation actions include habitat protection, strengthening anti-poaching efforts, and promoting responsible management of domestic cats and dogs in areas where Geoffroy’s cats are present.

Historically, Geoffroy’s cats were heavily exploited during the cat skin trade boom from the late 1960s to the 1980s. Their pelts were the second most common cat fur in the international fur market during this period. Since the 1980s, international trade has significantly declined, and commercial hunting on the scale of the past appears to have largely ceased. However, furs are still occasionally found in local markets, indicating some level of ongoing exploitation.

Forested habitat within the Geoffroy’s cat’s range is undergoing rapid loss due to deforestation, posing a long-term threat. However, recent studies in Argentina suggest that this adaptable species may be able to utilize the resulting open areas, highlighting their capacity to adjust to changing landscapes, although the long-term consequences of such adaptations require further investigation.

Read more about the ethical considerations of keeping Wild Cats As Pets.

Range map data from IUCN Red List (2018)

Updated 2018