H.P. Lovecraft, a name synonymous with cosmic horror, is often lauded for his chilling tales and intricate mythos. However, alongside the appreciation for his literary contributions, there exists a critical examination of his personal views and how they permeated his work. One particularly striking example of this intersection is the name of a cat in his story “The Rats in the Walls”: “Nigger-Man.” This article delves into the history of this name, its context within Lovecraft’s life and times, and the subsequent editorial decisions and adaptations that have grappled with its deeply problematic nature.

In “The Rats in the Walls,” originally published in Weird Tales in 1924, the narrator recounts his household, explicitly mentioning, “My eldest cat, ‘Nigger-Man’, was seven years old.” This was not merely a fictional creation for Lovecraft. As evidenced in his letters, “Nigger-Man” was the actual name of his childhood pet cat.

As I have said, I moved in on July 16, 1923. My household consisted of seven servants and nine cats, of which latter species I am particularly fond. My eldest cat, “Nigger-Man”, was seven years old and had come with me from my home in Bolton, Massachusetts; the others I had accumulated whilst living with Capt. Norrys’ family during the restoration of the priory.

This personal connection to the name adds a layer of complexity to its presence in his fiction. Lovecraft’s cat was not just a plot device but seemingly a reflection of his lived reality. Letters reveal that the cat, often referred to as “Nig” for short, was a significant part of his early life. The first recorded mention dates back to a letter from Lovecraft’s grandfather in 1895. While it remains uncertain whether young Lovecraft himself coined the name, it is clear that the adults in his life accepted and used it.

The term, deeply offensive today, was, unfortunately, not uncommon as a name for black animals during that period. Even the cat aboard Robert Falcon Scott’s Terra Nova expedition in the early 1910s bore the same name. While societal attitudes were evolving, particularly after World War II, the casual use of such language highlights a starkly different era.

However, by 1956, when “The Rats in the Walls” was reprinted in Zest: The Magazine for Men, times had shifted enough for editorial intervention. In this version, “Nigger-Man” was changed to the arguably less loaded, though still somewhat generic, “Black Tom.”

I moved in on July 16, 1953. My household consisted of seven servants and nine cats, of which latter species I am particularly fond. My eldest cat, Black Tom, was seven years old and had come with me from my home in Bolton, Massachusetts; the others I had accumulated while living with Capt Norrys’ family during the restoration of the priory.

This alteration reflects a growing awareness of the racial insensitivity of the original name, even within the context of a men’s magazine aiming for “adult entertainment.” Zest‘s decision to modify the name underscores a changing cultural landscape where such blatant racial slurs were becoming less acceptable in mainstream publications. This editorial change, however, was an outlier for many years.

While Lovecraft’s personal racism is often discussed in relation to his private writings, the overt use of the slur in “The Rats in the Walls” presents a direct encounter with this aspect in his fiction. Although Lovecraft employed the specific slur “nigger” relatively infrequently in his published stories—approximately 31 times across five tales, with 19 instances in “The Rats in the Walls”—its impact is undeniable. His other works, such as The Case of Charles Dexter Ward, also feature similar names like “Nig,” further cementing the connection between his personal life, racial biases, and fictional creations.

It is important to distinguish between Lovecraft using such terms to depict racist characters and employing them in ways that seem to stem from his own worldview. In the case of “Nigger-Man,” it appears to be less about portraying a racist character within the narrative and more about reflecting a common, albeit deeply offensive, naming convention of his time, rooted in his personal life. This is further supported by Lovecraft’s later life references to black cats by similar names, as seen in a letter to Duane W. Rimel in 1934 where he mentions calling a cat “Old Nigger Man” alongside other epithets. This indicates a continued, if perhaps less explicitly stated, association in his mind.

The Zest magazine alteration to “Black Tom” represents an early attempt at sanitizing Lovecraft’s work in response to evolving social sensitivities. However, this version remains largely outside the main textual tradition of “The Rats in the Walls.” Arkham House, the primary publisher of Lovecraft’s work for decades after his death, never adopted the “Black Tom” name. Even a subsequent reprint in another men’s magazine, Sensation, retained the original name, albeit within a heavily edited and condensed version of the story.

The resistance to changing the name before the 1970s primarily came from Arkham House’s control over Lovecraft’s copyrights and a growing “pure text” movement among Lovecraft scholars and fans. This movement advocated for reading Lovecraft as he originally wrote, “warts and all,” pushing back against editorial revisions and bowdlerizations. This desire for textual fidelity clashed directly with growing social discomfort with racist language.

However, in adaptations and translations, the approach has been far more varied. Maria Luisa Bonfanti’s Italian translation rendered the name as “Moro” (“Moor”), while Jacques Papy’s French translation used “Négrillon” (“Pickaninny”). Comic adaptations have taken even more liberties: Bob Jennings’ Creepy comic renamed the cat “Salem,” Richard Corben’s Skull Comix used “Nigaman,” Vicente Navarro and Adolfo Usero’s Spanish adaptation opted for “Negro” (“Black”), and Horacio Lalia’s version used “Blakie” or “Blackie.” Dan Lockwood’s The Lovecraft Anthology Vol. 1 simply omitted the name entirely.

These varied approaches highlight the discomfort and complexity surrounding the original name. Adaptors and translators grapple with whether to preserve the historical accuracy, reflect the offensive nature in a different linguistic context, or sidestep the issue altogether.

The adaptation by Navarro & Usero in Lovecraft Un Homenaje en 15 Historietas, showcasing the name rendered as “Negro,” demonstrates one approach to translating the problematic name.

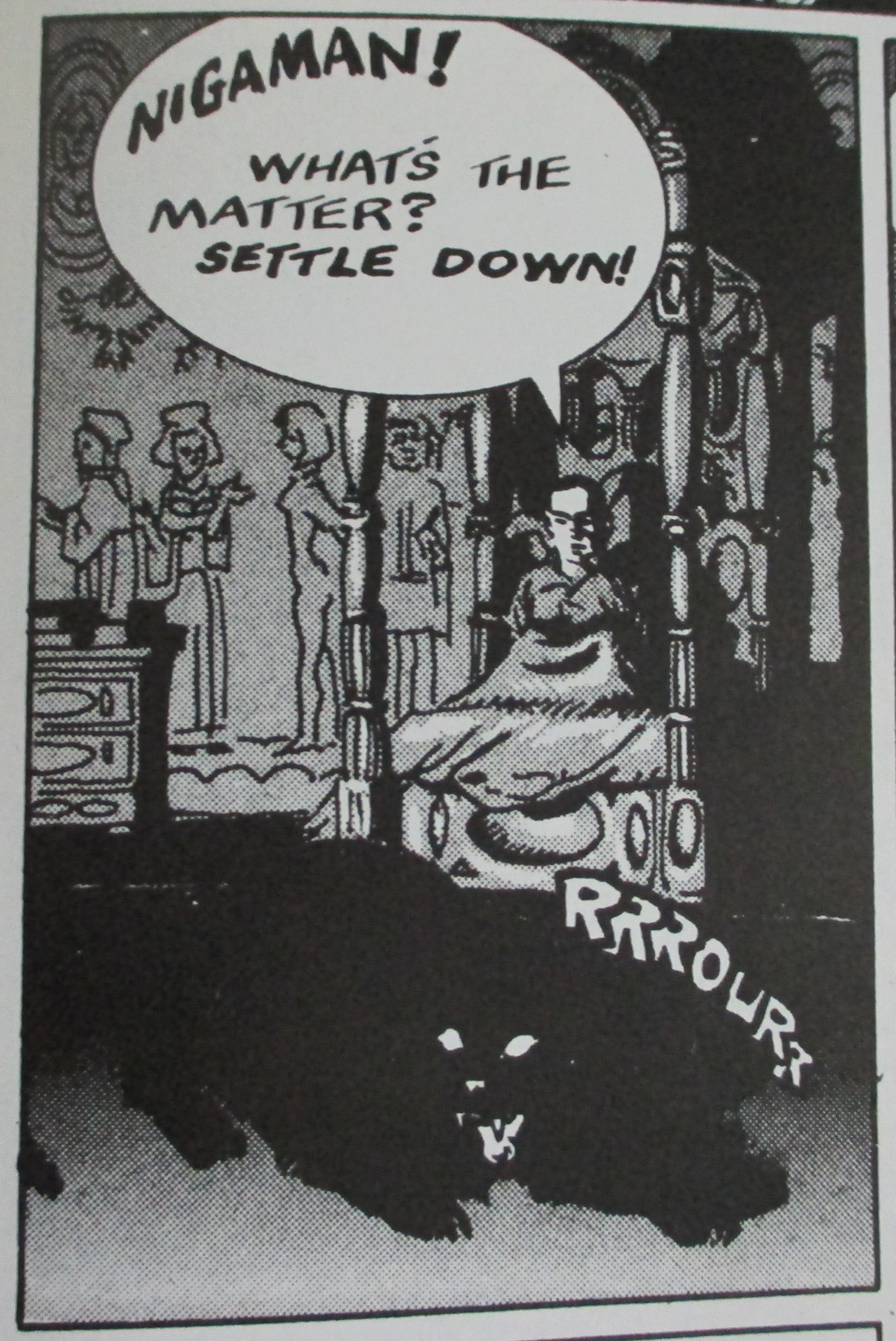

Richard Corben’s Skull Comix adaptation, using the name “Nigaman,” takes a different approach, seemingly attempting to retain a phonetic echo of the original while altering the spelling.

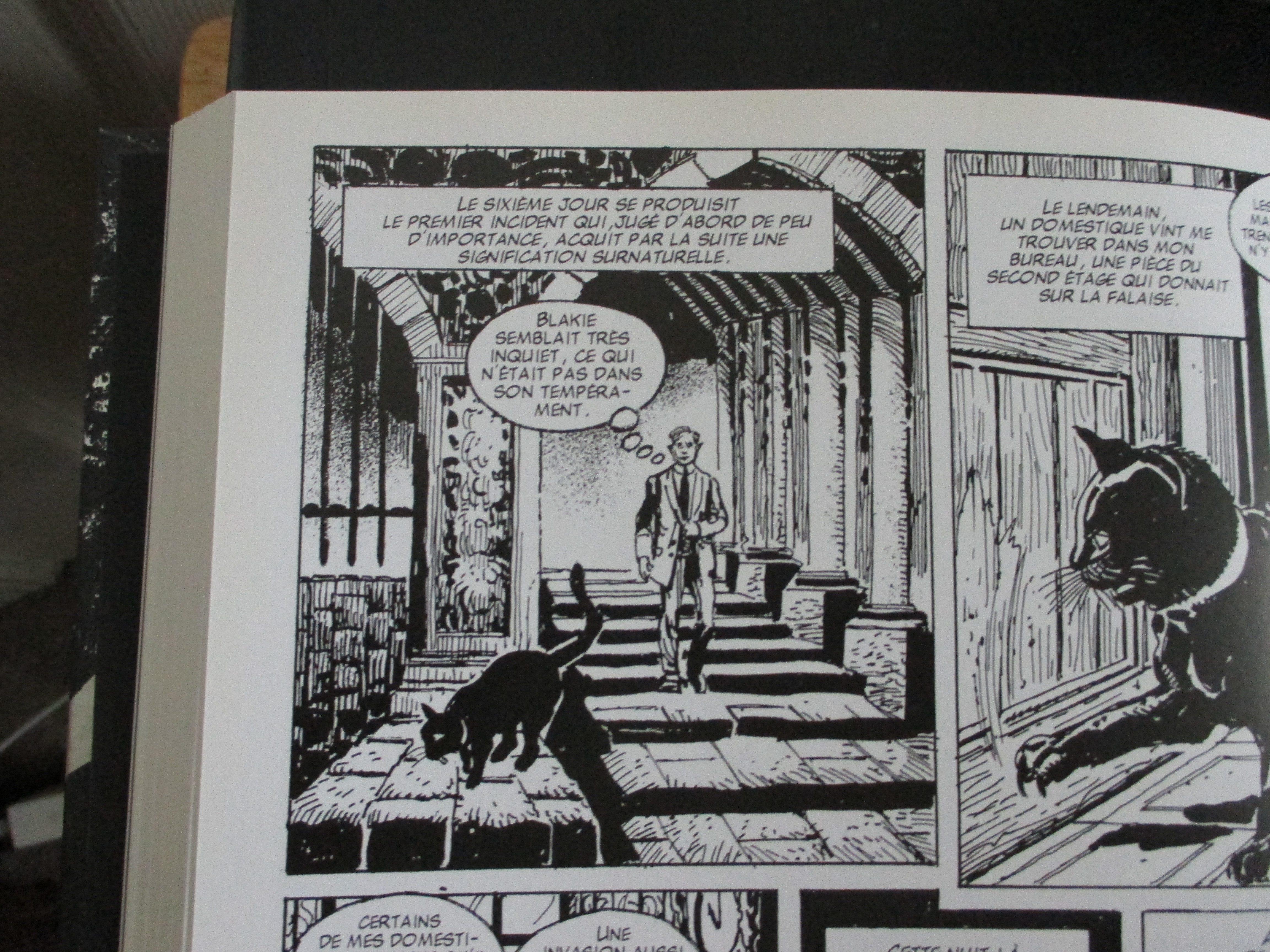

Horacio Lalia’s adaptation, opting for “Blakie” or “Blackie,” chooses a more sanitized and common pet name, completely avoiding the racial connotations of the original.

This inconsistency underscores the core issue: the name “Nigger-Man” carries no narrative significance within “The Rats in the Walls” beyond its shock value and connection to Lovecraft’s personal life. Its presence is primarily relevant to understanding Lovecraft’s historical context and the evolution of societal attitudes towards race.

Some critics and editors have chosen to exclude stories featuring such overtly racist elements. For example, “The Rats in the Walls” was omitted from a collection of Lovecraft’s Gothic tales due to its “casual racist remarks or allusions that make contemporary reprintings problematic.” This “problematic” nature reflects the potential offense to modern readers, not an actual impediment to reprinting, as the story remains widely available and frequently republished.

The debate around sanitizing or censoring older works is not unique to Lovecraft. Authors like Roald Dahl, Ian Fleming, and Agatha Christie have faced similar scrutiny, with discussions about updating or removing language deemed offensive by contemporary standards. In Christie’s case, even titles like And Then There Were None (originally Ten Little Niggers) have been changed over time, acknowledging the evolving understanding of racial slurs.

These authors, including Lovecraft, were products of eras where racism and prejudice were more ingrained and accepted. Their continued readership today necessitates a critical engagement with these problematic aspects of their work. While business considerations may drive some editorial changes, a purely sanitized approach risks erasing historical context and hindering genuine understanding.

As the Zest version demonstrates, attempts to completely erase or alter such elements often prove superficial and ultimately less impactful than confronting the original text directly. Excluding “The Rats in the Walls” from a collection due to its offensive name, as in the Gothic tales example, is arguably a disservice to readers and a missed opportunity for education.

Reprinting Lovecraft’s “The Rats in the Walls” with its original, offensive cat’s name provides a crucial educational opportunity. It allows for open discussion about historical racism, Lovecraft’s personal biases, and the evolution of societal norms. Removing the name, while perhaps intended to protect modern sensibilities, inadvertently removes a potent point of engagement with these complex issues. In an age where Lovecraft’s works are in the public domain, the freedom to adapt and reinterpret exists alongside the responsibility to engage honestly and critically with the original texts, “warts and all,” including the uncomfortable reality of “Hp Lovecrafts Cats Name.”