First Edition of Cat's Cradle by Kurt Vonnegut

First Edition of Cat's Cradle by Kurt Vonnegut

Published in 1963, amidst the chilling backdrop of the Cold War, Kurt Vonnegut’s Cat’s Cradle stands as a darkly humorous and profoundly insightful satire. This fourth novel by Vonnegut is often lauded as a cornerstone of 20th-century satirical literature, earning him comparisons to Mark Twain, albeit with a more encompassing societal critique. While Twain dissected specific societal flaws, Vonnegut broadened his scope to examine the absurdities of modern society and its collective values with equal wit and incisive observation.

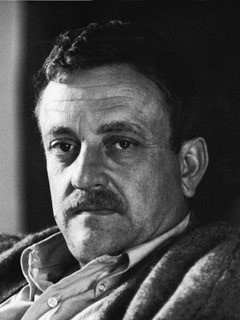

Kurt Vonnegut in 1963

Kurt Vonnegut in 1963

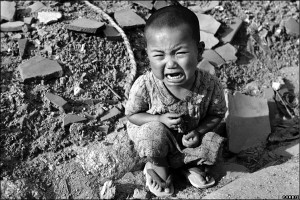

Cat’s Cradle immediately draws readers into its unique narrative style, opening with the narrator, Jonah – an echo of Melville’s Moby Dick – positioning himself as an initially detached observer. Jonah embarks on a quest to document the atmosphere surrounding the day of the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, not from the perspective of the victims, but from the American viewpoint. This sets the stage for Vonnegut’s exploration of moral detachment and the ease with which humanity can inflict destruction from a distance.

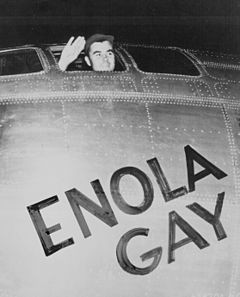

Enola Gay pilot Paul Tibbets waving

Enola Gay pilot Paul Tibbets waving

Vonnegut poignantly contrasts the impersonal act of dropping a bomb from high altitude with the visceral reality of face-to-face combat. He suggests that the emotional and moral consequences are far easier to ignore when destruction is delivered remotely, a chilling commentary on the nature of modern warfare and technological advancement.

Hiroshima after the atomic bombing

Hiroshima after the atomic bombing

Jonah’s pursuit of understanding leads him to the children of Felix Hoenikker, a fictional co-inventor of the atomic bomb. Hoenikker’s legacy is central to the novel’s exploration of scientific responsibility and unintended consequences. His children – Frank, Angela, and Newt – each embody different facets of Hoenikker’s detached genius and its ramifications. Newt, the diminutive youngest son, plays a crucial role in revealing a key thematic element. He recounts a chilling anecdote: when questioned about his reaction to the atomic bomb’s success, Hoenikker’s response to a scientist, reminiscent of Robert Oppenheimer, lamenting the “sin” of their creation, was a simple, unsettling question: “What is sin?”

J. Robert Oppenheimer at Los Alamos

J. Robert Oppenheimer at Los Alamos

This pivotal scene highlights Hoenikker’s profound detachment from the moral implications of his work. The novel’s title, Cat’s Cradle, emerges from this context: Hoenikker was reportedly playing the children’s string game during the atomic bomb test, symbolizing his and perhaps humanity’s disconnection from the devastating repercussions of scientific progress. This detachment is further emphasized by Vonnegut’s own background. Prior to becoming a celebrated author, Vonnegut worked for General Electric, tasked with humanizing their scientists. This experience provided him with firsthand insight into the culture of scientific research, where intellectual curiosity and innovation could sometimes overshadow ethical considerations. He witnessed the potential for science to produce both beneficial and catastrophically destructive outcomes, particularly if such discoveries fell into irresponsible hands.

In Cat’s Cradle, Hoenikker’s legacy extends beyond the atomic bomb to “Ice-9,” a fictional substance he invents seemingly as an intellectual exercise. Ice-9 possesses the alarming property of turning any water it contacts into solid ice, with potentially apocalyptic consequences. This invention becomes a central plot device, underscoring the theme of unchecked scientific innovation.

The narrative follows Jonah as he travels with Angela and Newt Hoenikker to the fictional Caribbean island of San Lorenzo. There, Frank, the eldest brother, holds a position of power as Major General under the island’s ailing dictator, Papa Monzano. Frank’s ambition positions him as the likely successor, further intertwining the Hoenikker family with the fate of San Lorenzo.

Throughout Jonah’s experiences on San Lorenzo, Vonnegut masterfully satirizes not only science but also religion and government. Jonah discovers that each Hoenikker child possesses a sample of Ice-9, raising the stakes and hinting at impending global disaster. The novel subtly questions the role of divine intervention in a world teetering on self-destruction.

Vonnegut’s own evolving views on religion, ranging from belief to agnosticism to atheism, are reflected in the novel’s portrayal of Bokononism, San Lorenzo’s unique and paradoxical religion. Bokonon, a mischievous figure, preaches that all religions are built on “foma” – harmless untruths. Yet, Bokononism, despite its declared falsehood, provides solace and meaning to the islanders. Vonnegut’s satire here isn’t a simple dismissal of religion but a nuanced exploration of humanity’s need for belief systems, even if those systems are knowingly constructed. God, in Vonnegut’s vision within Cat’s Cradle, isn’t necessarily absent but perhaps indifferent, having given humanity the tools to thrive and now leaving them to their own devices – for better or worse.

This “hands-off” deity concept leads to a crucial Vonnegutian premise: humanity is perfectly capable of creating chaos and destroying a world that was initially “working just fine.” San Lorenzo’s government is ostensibly Christian, while Bokononism is practiced in secret, punishable by “the Hook,” a brutal execution method. Ironically, Papa Monzano, the dictator, is aware of the widespread practice of Bokononism but turns a blind eye. The Books of Bokonon, though forbidden, are ubiquitous, hand-copied and treasured, containing subversive truths about the absurdity of life and societal conventions. Bokononism’s central tenet – “Don’t take anything seriously” – reflects Vonnegut’s broader satirical approach and existential outlook.

Ultimately, Cat’s Cradle suggests that humanity’s predicament is self-inflicted. No external divine force, good or evil, is necessary for our downfall. We are perfectly capable of “hanging ourselves” through our own actions and inventions. Vonnegut’s satire transcends simple condemnation of science, religion, or government. Instead, he presents a cautionary tale urging humanity to be mindful of its desires and the potential consequences of its creations.

The enduring appeal of Cat’s Cradle lies in its darkly humorous yet profoundly relevant commentary on modern existence. As the original article’s author reflects on their youthful encounter with the book, and its newfound appreciation by a younger generation, it’s clear that Cat’s Cradle continues to resonate across generations. Its exploration of scientific responsibility, existential angst, and the search for meaning in an absurd world remains strikingly pertinent today. Vonnegut’s satirical masterpiece serves as a timeless reminder of the delicate balance between human ingenuity and the potential for self-destruction.

So it goes.