When considering the concept of a God who is both all-loving and ever-present, it can be a daunting notion. This isn’t a deity focused on mere intellectual understanding, strict rituals, or even simple human kindness. Instead, it’s a God who seeks something far more profound: the genuine honesty that lies hidden deep within our hearts. This is a God who, like a persistent hunter, pursues even the most resistant among us, yet in ultimate surrender, waits with open arms. As a young person, this idea seemed foreign, relegated to the realms of fiction, myth, or perhaps distant religious dogma—certainly not something to be found in the local church or the tangible world around me.

However, the reality of God’s presence can arrive unexpectedly and profoundly. Like being caught unaware, one moment you’re moving along your chosen path, perhaps without clear direction, and the next, you’re drawn into an entirely different Way. This shift can be immediate and complete. Despite the world’s suffering and personal imperfections, the sense of transformation can be undeniable. Before realizing there was even a pursuit, one finds themselves willingly caught. For many, including myself, this capture is a source of profound joy.

C.S. Lewis, the celebrated author, captured a similar sentiment, though from a different perspective, when he described his own conversion experience. He famously likened the experience of God’s revelation not to a willing seeker finding their object of search, but rather to “the mouse’s search for the cat.” In his autobiography, Surprised by Joy, Lewis elaborates on this feeling:

“People who are naturally religious find difficulty in understanding the horror of such a revelation. Amiable agnostics will talk cheerfully about ‘man’s search for God.’ To me, as I then was, they might as well have talked about the mouse’s search for the cat” (Surprised by Joy, ch. XIV).

This analogy of the Cat And Mouse has always resonated deeply, though my personal encounter differed significantly from Lewis’s initial dread. While my experience of being “found” was overwhelmingly positive, Lewis’s perspective was marked by a lifelong awareness and fear of this very encounter. Imagine living with the sense of being pursued by something you simultaneously know and fear. Ultimately, however, this pursuit did reach Lewis, leading to his famous description of himself as “the most dejected and reluctant convert in all England” (Surprised by Joy, ch. XIV). This contrast highlights the complex and varied ways individuals experience the approach of faith, a journey often depicted through powerful metaphors like the cat and mouse game.

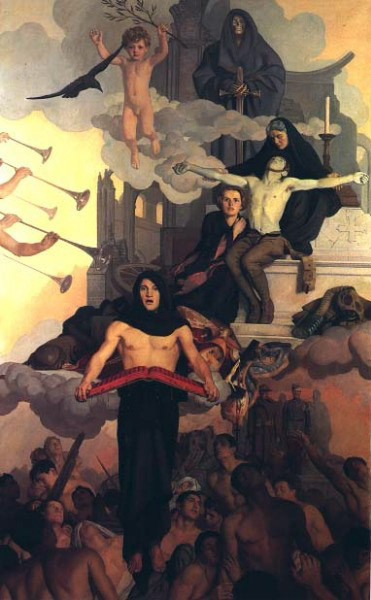

R.H. Ives Gammell's illustration of the Hound of Heaven pursuing a fleeing figure, capturing the poem's theme of relentless divine pursuit.

R.H. Ives Gammell's illustration of the Hound of Heaven pursuing a fleeing figure, capturing the poem's theme of relentless divine pursuit.

The image of the “Hound of Heaven” offers another compelling lens through which to understand this relentless divine pursuit. The phrase itself evokes a sense of inescapable seeking, and while I initially associated it with George MacDonald’s vision of heaven reaching into the darkest depths to find the lost, it actually originates from a popular Victorian Christian poem, “The Hound of Heaven” by Francis Thompson. The poem vividly portrays this divine pursuit. Its opening lines immediately bring to mind the persistent chase:

I fled Him, down the nights and down the days;

I fled Him, down the arches of the years;

I fled Him, down the labyrinthine ways

Of my own mind; and in the mist of tears

I hid from Him, and under running laughter.

Up vistaed hopes I sped;

And shot, precipitated,

Adown Titanic glooms of chasmèd fears,

From those strong Feet that followed, followed after.

But with unhurrying chase,

And unperturbèd pace,

Deliberate speed, majestic instancy,

They beat—and a Voice beat

More instant than the Feet—

‘All things betray thee, who betrayest Me.’

The parallel between Thompson’s “Hound of Heaven” and Lewis’s cat and mouse analogy is striking. Both capture the essence of a persistent, almost inevitable divine approach. Lewis himself further elaborated on this “unperturbèd pace” of God, comparing it to a chess game where he was perpetually on the losing side, move by move. Interestingly, in another context, Lewis also employed the image of mice freeing the great lion Aslan by gnawing through ropes, showcasing the unexpected power in seemingly weaker entities within a larger, divinely ordained plan.

For J.R.R. Tolkien, a contemporary of Lewis, the experience differed again. He described it not as a “Hound of Heaven” or a cat and mouse chase, but as “the never-ceasing silent appeal of Tabernacle, and the sense of starving hunger” (Letter 250, to Michael Tolkien). Tolkien’s perspective, focused on longing and the quiet call of religious structure, contrasts with both the pursuit imagery and my own experience, which was neither a hunt nor a lure. Instead, it was a dawning realization of a reality beyond the self, a discovery of a redemptive God already present in the universe.

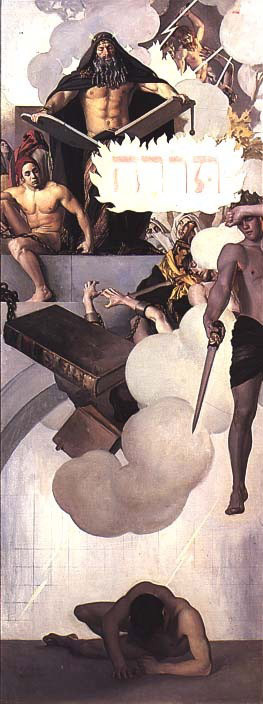

Ives Gammell's depiction of the Hound of Heaven's relentless pursuit through varied landscapes, symbolizing the omnipresent nature of divine seeking.

Ives Gammell's depiction of the Hound of Heaven's relentless pursuit through varied landscapes, symbolizing the omnipresent nature of divine seeking.

“The Hound of Heaven”

by Francis Thompson (1893)

I fled Him, down the nights and down the days;

I fled Him, down the arches of the years;

I fled Him, down the labyrinthine ways

Of my own mind; and in the mist of tears

I hid from Him, and under running laughter. 5

Up vistaed hopes I sped;

And shot, precipitated,

Adown Titanic glooms of chasmèd fears,

From those strong Feet that followed, followed after.

But with unhurrying chase, 10

And unperturbèd pace,

Deliberate speed, majestic instancy,

They beat—and a Voice beat

More instant than the Feet—

‘All things betray thee, who betrayest Me.’ 15I pleaded, outlaw-wise,

By many a hearted casement, curtained red,

Trellised with intertwining charities;

(For, though I knew His love Who followèd,

Yet was I sore adread 20

Lest, having Him, I must have naught beside).

But, if one little casement parted wide,

The gust of His approach would clash it to.

Fear wist not to evade, as Love wist to pursue.

Across the margent of the world I fled, 25

And troubled the gold gateways of the stars,

Smiting for shelter on their clangèd bars;

Fretted to dulcet jars

And silvern chatter the pale ports o’ the moon.

I said to Dawn: Be sudden—to Eve: Be soon; 30

With thy young skiey blossoms heap me over

From this tremendous Lover—

Float thy vague veil about me, lest He see!

I tempted all His servitors, but to find

My own betrayal in their constancy, 35

In faith to Him their fickleness to me,

Their traitorous trueness, and their loyal deceit.

To all swift things for swiftness did I sue;

Clung to the whistling mane of every wind.

But whether they swept, smoothly fleet, 40

The long savannahs of the blue;

Or whether, Thunder-driven,

They clanged his chariot ’thwart a heaven,

Plashy with flying lightnings round the spurn o’ their feet:—

Fear wist not to evade as Love wist to pursue. 45

Still with unhurrying chase,

And unperturbèd pace,

Deliberate speed, majestic instancy,

Came on the following Feet,

And a Voice above their beat— 50

‘Naught shelters thee, who wilt not shelter Me.’

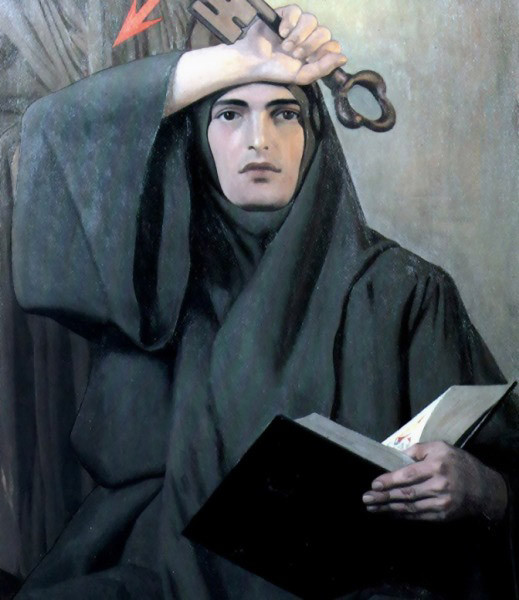

R.H. Ives Gammell's illustration portraying the speaker's futile attempts to hide from the Hound of Heaven, highlighting the poem's theme of divine inescapability.

R.H. Ives Gammell's illustration portraying the speaker's futile attempts to hide from the Hound of Heaven, highlighting the poem's theme of divine inescapability.

I sought no more that after which I strayed

In face of man or maid;

But still within the little children’s eyes

Seems something, something that replies, 55

They at least are for me, surely for me!I turned me to them very wistfully;

But just as their young eyes grew sudden fair

With dawning answers there,

Their angel plucked them from me by the hair. 60

‘Come then, ye other children, Nature’s—share

With me’ (said I) ‘your delicate fellowship;

Let me greet you lip to lip,

Let me twine with you caresses, Wantoning 65

With our Lady-Mother’s vagrant tresses,

Banqueting

With her in her wind-walled palace,

Underneath her azured daïs,

Quaffing, as your taintless way is, 70

From a chalice

Lucent-weeping out of the dayspring.’

So it was done: I in their delicate fellowship was one—

Drew the bolt of Nature’s secrecies. 75

I knew all the swift importings

On the wilful face of skies;

I knew how the clouds arise

Spumèd of the wild sea-snortings;

All that’s born or dies 80

Rose and drooped with; made them shapers

Of mine own moods, or wailful or divine;

With them joyed and was bereaven.

I was heavy with the even,

When she lit her glimmering tapers 85

Round the day’s dead sanctities.

I laughed in the morning’s eyes.

I triumphed and I saddened with all weather,

Heaven and I wept together,

And its sweet tears were salt with mortal mine; 90

Against the red throb of its sunset-heart

I laid my own to beat,

And share commingling heat;

But not by that, by that, was eased my human smart.

In vain my tears were wet on Heaven’s grey cheek. 95

For ah! we know not what each other says,

These things and I; in sound I speak—

Their sound is but their stir, they speak by silences.

Nature, poor stepdame, cannot slake my drouth;

Let her, if she would owe me, 100

Drop yon blue bosom-veil of sky, and show me

The breasts o’ her tenderness:

Never did any milk of hers once bless

My thirsting mouth.

Nigh and nigh draws the chase, 105

With unperturbèd pace,

A panel from R.H. Ives Gammell's series, illustrating the Hound of Heaven's presence drawing closer, signifying the growing awareness of divine pursuit.

A panel from R.H. Ives Gammell's series, illustrating the Hound of Heaven's presence drawing closer, signifying the growing awareness of divine pursuit.

Deliberate speed, majestic instancy

And past those noisèd Feet

A voice comes yet more fleet—

‘Lo! naught contents thee, who content’st not Me!’ 110

Naked I wait Thy love’s uplifted stroke!

My harness piece by piece Thou hast hewn from me,

And smitten me to my knee;

I am defenceless utterly.

I slept, methinks, and woke, 115

And, slowly gazing, find me stripped in sleep.

In the rash lustihead of my young powers,

I shook the pillaring hours

And pulled my life upon me; grimed with smears,

I stand amid the dust o’ the mounded years— 120

My mangled youth lies dead beneath the heap.

My days have crackled and gone up in smoke,

Have puffed and burst as sun-starts on a stream.

Yea, faileth now even dream

The dreamer, and the lute the lutanist; 125

Even the linked fantasies, in whose blossomy twist

I swung the earth a trinket at my wrist,

Are yielding; cords of all too weak account

For earth with heavy griefs so overplussed.

Ah! is Thy love indeed 130

A weed, albeit an amaranthine weed,

Suffering no flowers except its own to mount?

Ah! must— Designer infinite!—

Ah, must Thou char the wood ere Thou canst limn with it? 135

My freshness spent its wavering shower i’ the dust;

And now my heart is as a broken fount,

Wherein tear-drippings stagnate, spilt down ever

From the dank thoughts that shiver

Upon the sighful branches of my mind. 140

Such is; what is to be?

The pulp so bitter, how shall taste the rind?

I dimly guess what Time in mists confounds;

Yet ever and anon a trumpet sounds

From the hid battlements of Eternity; 145

Those shaken mists a space unsettle, then

Round the half-glimpsèd turrets slowly wash again.

But not ere him who summoneth I first have seen, enwound

With glooming robes purpureal, cypress-crowned; 150

His name I know, and what his trumpet saith.

Whether man’s heart or life it be which yields

Thee harvest, must Thy harvest-fields

Be dunged with rotten death?Now of that long pursuit 155

Comes on at hand the bruit;

That Voice is round me like a bursting sea:

‘And is thy earth so marred,

Shattered in shard on shard?

Lo, all things fly thee, for thou fliest Me! 160

Strange, piteous, futile thing!

Wherefore should any set thee love apart?

Seeing none but I makes much of naught’ (He said),

‘And human love needs human meriting:

How hast thou merited— 165

Of all man’s clotted clay the dingiest clot?

Alack, thou knowest not

How little worthy of any love thou art!

Whom wilt thou find to love ignoble thee,

Save Me, save only Me? 170

All which I took from thee I did but take,

Not for thy harms,

But just that thou might’st seek it in My arms.

All which thy child’s mistake

Fancies as lost, I have stored for thee at home: 175

Rise, clasp My hand, and come!’

Halts by me that footfall:

Is my gloom, after all,

Shade of His hand, outstretched caressingly?

‘Ah, fondest, blindest, weakest, 180

I am He Whom thou seekest!

Thou dravest love from thee, who dravest Me.’

Illustrations by R. H. Ives Gammel from A Pictorial Sequence Painted by R. H. Ives Gammell Based on The Hound of Heaven.