Heathcliff. The name itself might conjure up images of a simple, mischievous orange cat, perhaps a slightly less famous cousin of Garfield. For decades, Heathcliff has graced the newspaper comic pages, seemingly a staple of lighthearted, family-friendly humor. But beneath the surface of this seemingly straightforward comic strip lies a world of delightful absurdity, especially in its modern iteration helmed by Peter Gallagher. This isn’t your grandma’s Heathcliff comic anymore. It’s weirder, funnier, and arguably, a stroke of genius in its own right.

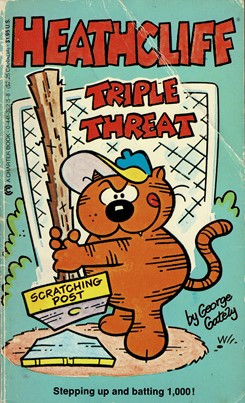

To truly understand the modern Heathcliff comic strip, one must first appreciate its origins. Created by George Gately, Heathcliff debuted as a single-panel comic in 1973. These early comics, often collected in paperbacks, presented a more traditional, albeit still mischievous, feline character. Many readers, like the author himself, may have stumbled upon Heathcliff through these paperback collections, perhaps even owning a copy of Heathcliff: Triple Threat, featuring the iconic image of Heathcliff wielding a scratching post like a baseball bat. These early strips established Heathcliff as a recognizable character in the crowded landscape of newspaper comics.

Heathcliff Triple Threat paperback cover, highlighting Heathcliff wielding a scratching post as a baseball bat, a classic image from the early comics

Heathcliff Triple Threat paperback cover, highlighting Heathcliff wielding a scratching post as a baseball bat, a classic image from the early comics

The 1980s saw Heathcliff expand beyond the newspaper page with animated adaptations. While these cartoons further cemented Heathcliff’s place in popular culture, they arguably didn’t capture the unique strangeness that would later define the comic strip. The most memorable aspect of the cartoon might be the Catillac Cats segment, featuring a group of cool cats, a far cry from the single-panel absurdity that was brewing in the comic strip’s future.

The real transformation of Heathcliff began in 1998 when Peter Gallagher, nephew of George Gately and John Gallagher, took over the reins of the comic strip. It’s from this point onwards that Heathcliff started its journey into the wonderfully bizarre. While the transition might have been gradual, by the 2010s, a distinct shift in tone and humor became undeniably apparent. This wasn’t just Heathcliff being a cat anymore; it was Heathcliff existing in a world where logic took a backseat to the delightfully illogical.

Example of Peter Gallagher's Heathcliff comic, depicting Heathcliff wearing jeans, illustrating the strip's shift to more surreal and contemporary humor

Example of Peter Gallagher's Heathcliff comic, depicting Heathcliff wearing jeans, illustrating the strip's shift to more surreal and contemporary humor

The modern Heathcliff comic, especially those from the late 2010s onwards, embrace a form of humor that can be described as absurdist, repetitive, and strangely captivating. One of the hallmarks of Gallagher’s Heathcliff is the recurring thematic elements. These aren’t just running gags; they are deep dives into bizarre concepts, explored week after week with subtle variations and unexpected twists. Themes like dirt, helmets, and even the mysterious Garbage Ape become recurring motifs, creating a unique and internally consistent, albeit utterly nonsensical, world within the comic strip.

Take, for example, the “dirt” theme. A week of Heathcliff comics might be dedicated to exploring the many facets of dirt, from dirt bombs to simply contemplating the nature of dirt itself. This might seem random, but it’s in this dedication to the absurd that the humor lies. It’s not about punchlines in the traditional sense; it’s about immersing yourself in a world where dirt can be a central comedic focus.

Heathcliff comic strip panel featuring the caption 'Children love the meat tank', showcasing the strip's absurd humor.

Heathcliff comic strip panel featuring the caption 'Children love the meat tank', showcasing the strip's absurd humor.

Similarly, the “helmet” theme, often featuring helmets emblazoned with words like “HAM” or “MEAT,” adds another layer of delightful strangeness. These helmets appear without explanation, their purpose ambiguous, their presence simply accepted as part of the Heathcliff universe. The humor isn’t derived from understanding why Heathcliff is wearing a helmet with “MEAT” on it, but rather from the sheer unexpectedness and repetition of the image.

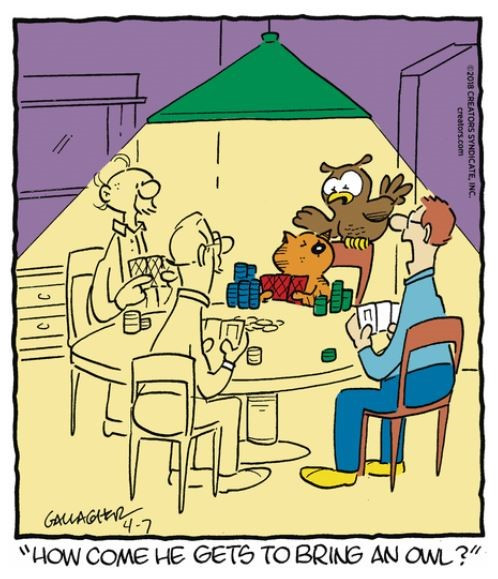

Heathcliff comic panel where Heathcliff brings an owl to a poker game as an advisor, exemplifying the unexpected and bizarre scenarios in the modern strip.

Heathcliff comic panel where Heathcliff brings an owl to a poker game as an advisor, exemplifying the unexpected and bizarre scenarios in the modern strip.

This repetitive, thematic approach to humor creates a sense of shared inside jokes with the reader. As you delve deeper into Peter Gallagher’s Heathcliff, you begin to recognize these recurring motifs, anticipating their return and finding humor in their subtle variations. It’s akin to developing a unique language with the cartoonist, where understanding isn’t about deciphering a punchline but about recognizing and appreciating the recurring elements of this strange comedic world.

This style of humor isn’t for everyone, and indeed, it has its detractors. Some critics find the modern Heathcliff to be unfunny, dated, and lacking in traditional comedic structure. They might argue that the humor is simply “random” or “absurd for the sake of being absurd,” missing the intentionality and unique comedic voice that Gallagher has cultivated. One such dissenting voice, cartoonist Josh Pettinger, openly admits his dislike for the current Heathcliff, finding it “offensively unfunny” and the humor “patronizing,” suggesting it’s just “Here’s a thing, and here’s another thing, these two things don’t normally go together, but here they are together, isn’t that funny?”.

However, this criticism arguably misses the point of Gallagher’s comedic approach. It’s not about delivering traditional jokes with clear setups and punchlines. It’s about creating a sustained mood of absurdity, a world where the unexpected is the norm, and humor arises from the constant subversion of expectations. The lack of explicit jokes is precisely the joke itself. It’s a commentary on the very nature of humor and the often-arbitrary ways in which we find things funny.

Heathcliff comic strip panel with the phrase 'emotional meat', embodying the abstract and often puzzling humor characteristic of Peter Gallagher's work.

Heathcliff comic strip panel with the phrase 'emotional meat', embodying the abstract and often puzzling humor characteristic of Peter Gallagher's work.

In contrast to the critics, many readers, and even fellow cartoonists, find the modern Heathcliff to be genuinely innovative and hilarious. They appreciate the confidence with which Gallagher embraces the absurd, his willingness to deviate from traditional comic strip conventions, and his ability to create humor that is both strange and surprisingly relatable. As cartoonist Andrew Neal notes, reading Heathcliff can feel like sharing “dozens of in-jokes” with a friend, a testament to the unique and engaging world Gallagher has built.

The appeal of Heathcliff also lies in its “unrepentant” nature, as described by Heathcliff fan Charles Roche. Heathcliff, in this modern iteration, is not trying to be likable or conventionally funny. He exists in his own world, driven by his own peculiar logic, and the humor arises from his unapologetic embrace of this absurdity. This “fuck you!” attitude, as Roche playfully puts it, is part of what makes Heathcliff so endearing. He’s a character who doesn’t care about making sense, and in a world that often demands conformity and rationality, there’s something liberating and funny about that.

Ultimately, the genius of Peter Gallagher’s Heathcliff lies in its ability to challenge our preconceived notions of what a comic strip can be. It’s not just about telling jokes; it’s about creating an experience, an invitation to step into a world where the rules of humor are different, where repetition and absurdity are celebrated, and where a fat orange cat can wear a helmet that says “MEAT” without explanation and still make you laugh. So, dive into the world of Heathcliff cat. Start reading, let the absurdity wash over you, and you might just find yourself becoming a convert to this wonderfully weird and undeniably hilarious comic strip.