Cats in the Middle Ages faced a contradictory reputation. Often viewed with suspicion due to their perceived links to paganism and witchcraft, these feline creatures were also surprisingly depicted in a playful and affectionate manner in medieval manuscripts. These charming portrayals offer valuable insights into medieval attitudes towards cats, revealing their significant presence in everyday life.

Despite the negative associations with the supernatural, medieval art and literature showcase that cats were indeed central to the medieval household. Understanding the medieval perspective on animals, particularly pets, is crucial to appreciating the status and role of cats during this period.

In medieval society, the animals people kept often served as identifiers of their social standing. Exotic pets like monkeys, imported from distant lands, were symbols of wealth and prestige. For the nobility, pets became extensions of personal identity. The act of lavishing attention, affection, and high-quality food on an animal that served no functional purpose beyond companionship was a clear marker of elevated status.

Consequently, it was common for high-status men and women in the Middle Ages to commission portraits of themselves alongside their pets, most frequently cats and dogs. These животные companions visually reinforced their noble status and portrayed them as individuals of leisure and affluence.

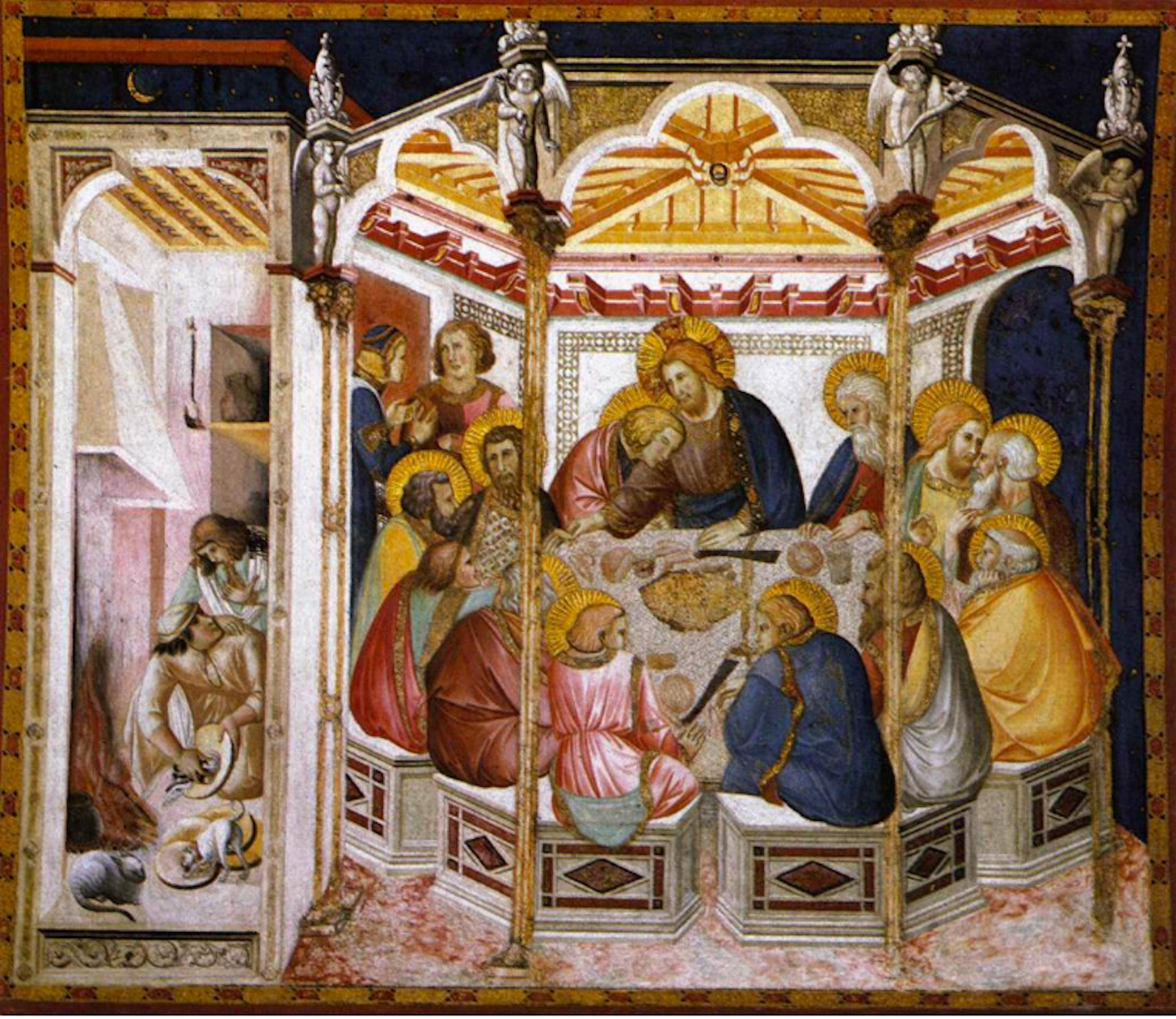

Medieval artwork depicting the Last Supper, with a cat and dog present in the domestic space outside the dining area.

Medieval artwork depicting the Last Supper, with a cat and dog present in the domestic space outside the dining area.

The presence of cats in iconography depicting feasts and other domestic scenes is commonplace, further solidifying their role as pets within the medieval home. Pietro Lorenzetti’s “Last Supper,” painted around 1320, provides a charming example. While the central focus is the biblical scene, a cat is subtly placed by the fire, while a dog is depicted licking a plate on the floor. These animals are not part of the narrative but serve to contextualize the scene within a domestic, familiar environment.

Similarly, within the illuminated pages of a Dutch Book of Hours, a prayer book popular in the Middle Ages, a cozy household scene unfolds. A man and woman are depicted in a domestic setting, while a well-fed cat observes the scene from the lower left corner. Again, the cat is not the focal point but is an accepted and integrated part of this medieval domestic space, adding a touch of everyday life to the religious manuscript.

An illustration from a Book of Hours circa 1500, showing a domestic scene with a cat observing a man and woman in a household setting.

An illustration from a Book of Hours circa 1500, showing a domestic scene with a cat observing a man and woman in a household setting.

Just as we do today, medieval families bestowed names upon their feline companions. Evidence from the 13th century Beaulieu Abbey reveals a cat named “Mite.” This affectionate name is recorded in green ink lettering beside a doodle of the cat itself, found in the margins of a medieval manuscript. This personal touch highlights the individual relationships people had with their cats.

Royal Treatment for Medieval Cats

Cats were not only present in medieval homes but also received considerable care. Early 13th-century accounts from the manor at Cuxham in Oxfordshire document the purchase of cheese specifically for a cat. This detail indicates that cats were not merely expected to fend for themselves as working animals, but were provided with specific provisions, suggesting a level of pet ownership and care.

Portrait of a young noblewoman affectionately holding a tabby kitten, emphasizing the bond between humans and cats in the Renaissance period.

Portrait of a young noblewoman affectionately holding a tabby kitten, emphasizing the bond between humans and cats in the Renaissance period.

Bacchiacca’s circa 1525 painting, “Portrait of a Young Lady Holding a Cat,” exemplifies the affectionate relationship between people and their cats.

Further demonstrating the esteemed position of cats in medieval society, Isabeau of Bavaria, the 14th-century Queen of France, was known for her extravagant spending on her pets. While squirrels also enjoyed royal pampering, cats were certainly not excluded. In 1406, the queen purchased bright green cloth specifically to create a special cover for her cat, showcasing the lengths to which the medieval elite would go to ensure the comfort and well-being of their feline companions.

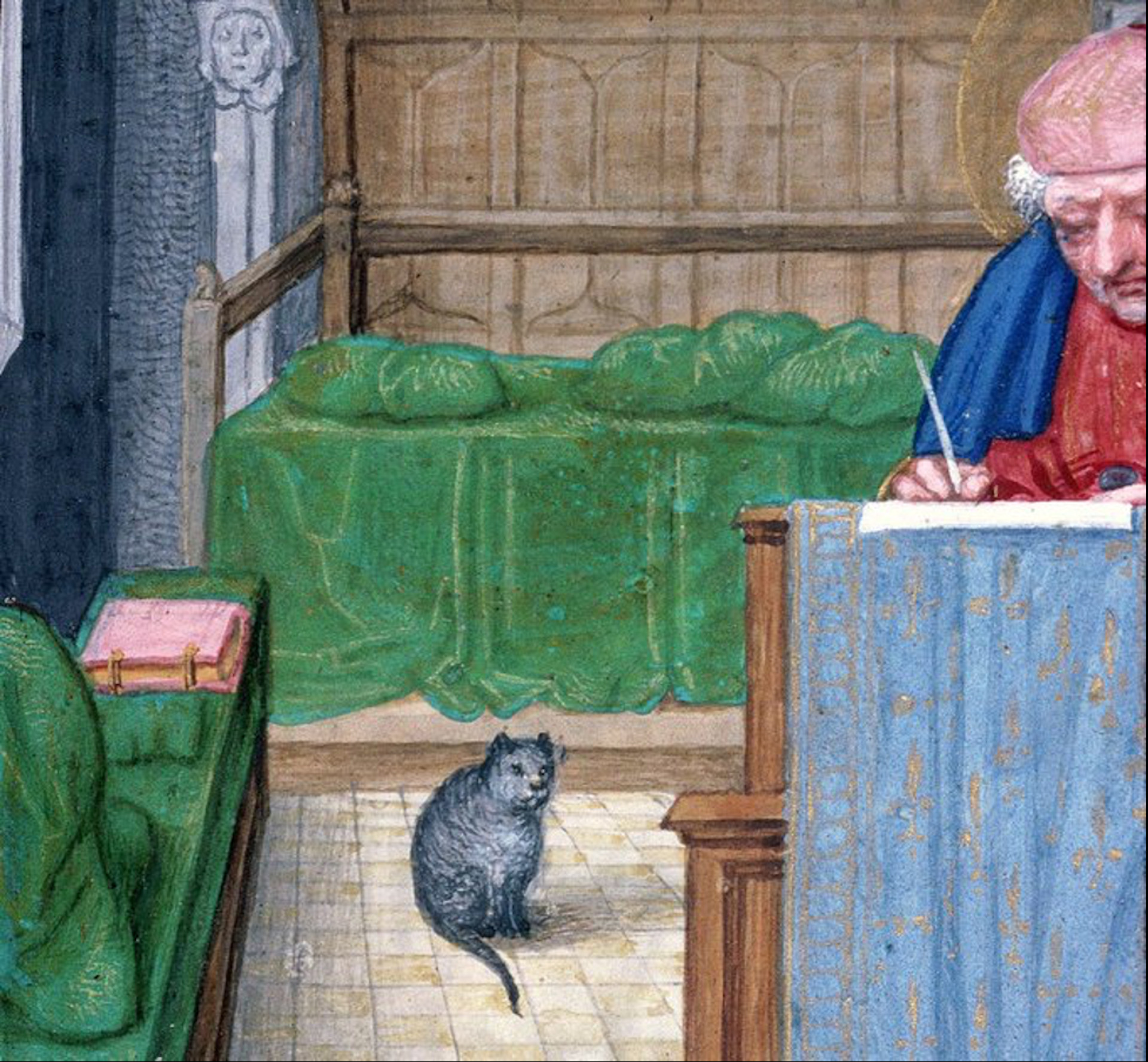

Beyond the nobility, cats were also cherished companions for scholars. Eulogies dedicated to cats were not uncommon by the 16th century. One such poem describes a cat as “a scholar’s light and dearest companion,” highlighting the emotional bond and the comfort cats brought to those engaged in intellectual pursuits. Cats offered not just companionship but also welcome breaks and stress relief from the demanding work of reading and writing.

Medieval Cats in the Cloisters: Status and Scrutiny

Cats also found their place within medieval religious spaces, often acting as status symbols even within cloisters. Numerous medieval manuscripts feature illuminations depicting nuns with cats, and playful cat doodles frequently appear in the margins of Books of Hours, suggesting their common presence in religious communities.

Illuminated manuscript showing St. Matthew with a cat, indicating the presence of cats even in religious contexts.

Illuminated manuscript showing St. Matthew with a cat, indicating the presence of cats even in religious contexts.

However, the presence of cats in religious settings was not without its critics. Sermon literature from the medieval period reveals disapproval of keeping cats in religious orders. John Bromyard, a 14th-century English preacher, deemed cats useless, overfed accessories of the wealthy, especially in contrast to the poverty surrounding them.

A detailed doodle from a medieval manuscript showing a nun spinning thread while her cat playfully interacts with the spindle.

A detailed doodle from a medieval manuscript showing a nun spinning thread while her cat playfully interacts with the spindle.

A 14th-century miniature from the Maastricht Hours depicting a nun spinning thread, with her pet cat playing with the spindle.

Furthermore, cats were sometimes associated with the devil in medieval thought. While their hunting prowess was admired, their stealth and cunning were not always viewed as positive traits for companions, contributing to negative perceptions. These associations led to instances of cats being killed, a practice that may have had detrimental consequences during outbreaks of the Black Death and other medieval plagues, as a larger cat population could have helped control flea-infested rat populations.

Despite these negative associations and criticisms, there is no evidence of formal rules prohibiting cats in religious communities. The very persistence of criticism against keeping cats in cloisters suggests that they were, in fact, quite common.

A whimsical doodle of a cat dressed as a nun in the margin of a medieval manuscript, highlighting the playful depiction of cats even in religious contexts.

A whimsical doodle of a cat dressed as a nun in the margin of a medieval manuscript, highlighting the playful depiction of cats even in religious contexts.

A playful medieval doodle of a cat cosplaying as a nun, showcasing the lighthearted portrayal of cats in manuscripts.

Even if not universally accepted in religious communities, the playful images of cats found in monasteries and other medieval art clearly demonstrate that they were generally well-cared for and even cherished.

Ultimately, cats were firmly at home in the medieval world. As evidenced by their playful and affectionate depictions in countless medieval manuscripts and artworks, the bond between our medieval ancestors and their cats was surprisingly similar to the relationships we share with our feline friends today.