Feline indolent ulcers, commonly known as rodent ulcers, are distinctive skin lesions that affect cats, particularly around the mouth. These ulcers are not caused by rodents, despite the name, but are a reaction pattern of the skin, often appearing on the upper lip, near the philtrum, or close to the canine teeth. Rodent ulcers can present themselves in various ways – symmetrically on both sides of the lip, asymmetrically, or just on one side. Interestingly, cats with rodent ulcers typically don’t show signs of pain or itchiness, and owners might only notice them incidentally. In some cases, the lymph nodes under the jaw may be enlarged. The age at which a cat might develop a rodent ulcer varies widely.

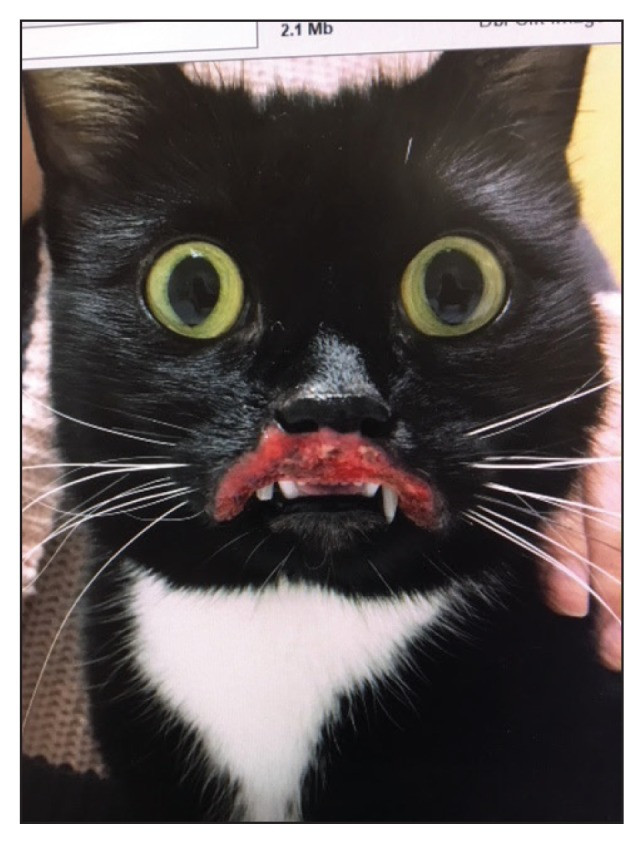

Clinically, feline rodent ulcers are characterized by crusting, redness (erythema), and sunken ulcers at the edge of the lip, as shown in Figure 1. These lesions can develop slowly over time or appear quite rapidly. Often, cat owners discover them during routine check-ups or when bringing their cat in for other skin issues, as the cat usually doesn’t seem bothered by the ulcer in its early stages. As the condition progresses, the ulcers can grow larger and deeper. Even with progression, rodent ulcers typically remain well-defined with raised borders surrounding a central, concave, ulcerated area of granulation tissue. This tissue might include yellow or white necrotic (dead) tissue. Due to the raised edges and significant local inflammation, these lesions can sometimes look like firm, growing, ulcerated masses. In some instances, pus-like discharge may be expressed from these lesions.

Figure 1

Figure 1

Figure 1: Indolent ulcer with bacterial infection before treatment, demonstrating typical lesion appearance.

While rodent ulcers have a recognizable visual appearance, simply identifying the lesion isn’t enough to determine the underlying cause. Like many skin conditions in cats, recognizing a rodent ulcer should prompt a treatment plan for the lip lesion itself, but more importantly, it should initiate a diagnostic investigation to find the primary causes that led to its development. The most common culprits behind rodent ulcers are allergic diseases. These include flea bite hypersensitivity, feline atopy (allergies to environmental substances other than fleas or food), insect bite hypersensitivity, and food allergies. When an allergy is suspected, it’s also important to consider the possibility of a secondary bacterial infection within the ulcer. Bacterial involvement is now understood to be more frequent than previously thought.

A critical differential diagnosis for feline rodent ulcers is squamous cell carcinoma (a type of skin cancer). Other conditions that need to be considered include fungal infections, feline herpes virus type 1 infection, trauma, lymphoma, and mast cell tumors. Histopathology, or microscopic examination of tissue samples, is crucial in differentiating rodent ulcers from these other diseases. Microscopic analysis of a rodent ulcer typically reveals epidermal hyperplasia (thickening of the outer layer of skin) and a significant infiltration of eosinophils (a type of white blood cell associated with allergies) in the dermis (deeper layer of skin). Other inflammatory cells may also be present. Sometimes, mucin deposition (a component of mucus) can be observed in the epidermis.

Diagnostic Workup for Rodent Ulcers in Cats

In many cases, a preliminary diagnosis of a rodent ulcer is made based on the characteristic appearance of the lesion. Even though these lesions strongly suggest an underlying allergy, especially in younger cats, it’s essential to consider other possibilities during the diagnostic process. The specific diagnostic tests chosen will depend on each cat’s individual situation and presenting symptoms.

A simple and useful initial diagnostic test is impression cytology of the lesion. This involves taking a sample from the surface of the ulcer to examine under a microscope. Cytology can help determine if a bacterial infection is present within the lesion. Typically, cytology of rodent ulcers shows eosinophilic inflammation and may reveal bacteria, with or without neutrophilic inflammation (another type of white blood cell response, often to bacteria). If an infection is detected, appropriate antibiotic therapy is necessary while investigating for underlying allergies. Rodent ulcers should be considered as potentially deep pyoderma (deep skin infection), so a course of antibiotics lasting 4 to 6 weeks might be needed. While some veterinary literature mentions empirical antibiotic use (antibiotics given without culture and sensitivity testing) as effective for some patients, this approach is generally discouraged due to growing concerns about antibiotic resistance in both animals and humans. Furthermore, published guidelines on antibiotic dosage and treatment duration for feline rodent ulcers are often quite general. A more reliable approach to determine the need for antibiotics and the length of treatment involves combining impression cytology, clinical assessment of the lesion, and bacterial culture and sensitivity testing.

As part of the initial allergy investigation, flea control for all pets in the household and a dietary elimination trial should be started. For the diet trial, either a novel single protein diet or a hydrolyzed protein diet is used.

A punch biopsy for histopathology is the definitive diagnostic test and helps rule out other conditions, particularly neoplasia (cancer). This is best done after ruling out superficial infection via impression cytology. When collecting a biopsy sample for histopathology, a sample for bacterial culture should also be taken to rule out deep pyoderma that might not have been evident on superficial cytology. If deep pyoderma is confirmed, culture-based antibiotic therapy will help resolve the infection.

Furthermore, a thorough dermatological and oral examination is crucial for all cats presenting with rodent ulcers. Since allergies are a common underlying cause, other signs suggestive of allergy might be present. Rodent ulcers are part of the feline Eosinophilic Granuloma Complex (EGC). Other manifestations of EGC include eosinophilic plaques and eosinophilic granulomas, which can affect the skin or oral cavity. These might occur together with rodent ulcers. Additional signs of feline allergic disease can include self-inflicted hair loss (bilaterally symmetrical alopecia on the belly), miliary dermatitis (small, crusty bumps on the skin), and generalized itching (over-grooming or head and neck scratching). While the absence of these additional signs doesn’t rule out allergies, their presence is very helpful in guiding the diagnostic and treatment plan.

Treatment of Indolent Ulcers in Cats

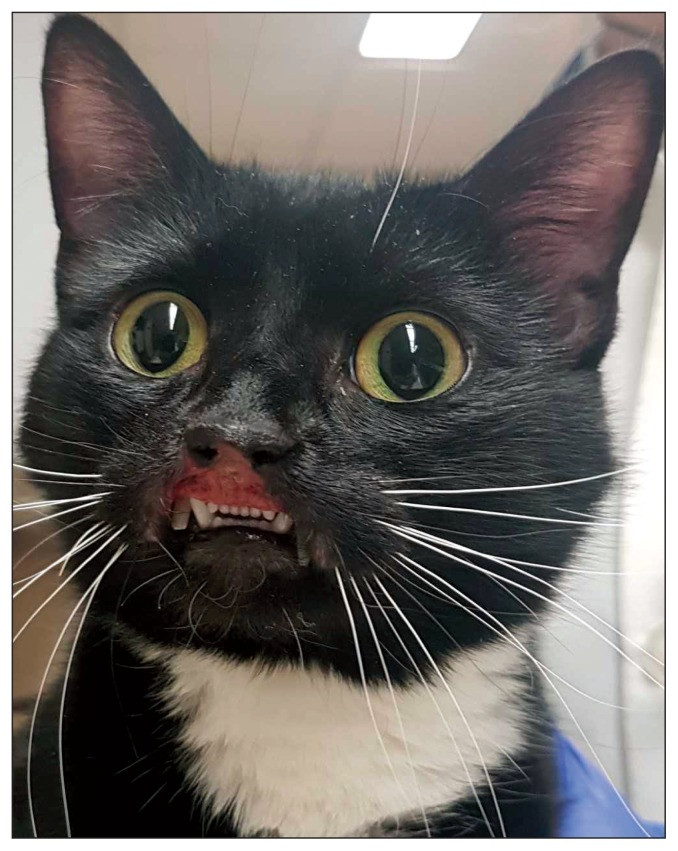

Various treatments have been described for rodent ulcers, including antibiotics, anti-inflammatory medications, and immunosuppressive therapies, as seen in Figure 2. As with many secondary issues related to allergies, these lesions respond better to treatment when the primary cause driving lesion formation is identified and managed. Since flea bite hypersensitivity is a known cause of rodent ulcers, effective flea control is a simple and effective treatment option for flea-allergic cats. All pets in the household should be treated for fleas, even if fleas aren’t obviously present. Dietary elimination trials followed by controlled food challenges can help diagnose or rule out food allergies. Food challenges are best performed after the lesion and any infection have resolved, and they are easier to evaluate when a previously itchy cat is no longer showing itchy behavior. If rodent ulcers (and other allergy signs) persist or recur despite appropriate investigations, environmental allergies (feline atopy) are likely. In atopic cats, intradermal allergy testing or serum allergy IgE testing should be performed to identify specific allergens, allowing for allergen-specific desensitization therapy (allergy shots or drops).

Figure 2

Figure 2

Figure 2: Indolent ulcer resolution after 4 weeks of dietary elimination trial and culture-based antibiotic therapy, showing improvement with appropriate treatment.

Symptomatic anti-inflammatory therapy can be used to help resolve the lesions while investigating the underlying cause. It’s important to remember that despite their striking appearance and ulceration, most cats with rodent ulcers appear comfortable, active, and maintain a good appetite. The term “indolent ulcer” itself comes from the Latin “indolens,” meaning “without pain.” Therefore, strong anti-inflammatory therapy shouldn’t be automatically assumed as necessary, especially as proper diagnostic workup and follow-up are essential. It’s also worth noting that appropriate antibiotic therapy alone can improve lesions, even without using glucocorticoids or cyclosporine, while allergy investigations are ongoing.

If a cat shows discomfort or additional clinical signs, corticosteroid therapy or cyclosporine therapy can be used to reduce inflammation associated with the lesion. However, lesions tend to recur when symptomatic therapy is reduced or stopped if the underlying cause hasn’t been addressed or if a secondary infection persists. Long-term immunosuppressive drug therapy is best avoided and should be replaced by thorough investigation of the primary underlying disease. Long-acting injectable corticosteroids, such as methylprednisolone acetate, should be avoided because the risk of side effects (like diabetes mellitus, urinary infections, heart problems, and fragile skin) often outweighs the severity of the rodent ulcer itself.

Other treatments reported to have occasional success include radiotherapy, cryosurgery, laser therapy, surgical removal, mixed bacterial vaccines, gold salt aurothioglucose, immunomodulating drugs like low-dose interferon alfa (oral or subcutaneous), and oral essential fatty acid supplementation.

Prognosis for Feline Rodent Ulcers

If the underlying cause of the rodent ulcer is identified and successfully managed, the prognosis for resolution is excellent. If the underlying cause remains uncontrolled, lesion recurrence is likely. Cats with recurring lesions for whom no underlying cause can be found often require long-term drug therapy to keep the lesions in remission. These cats have a less favorable prognosis as they may become resistant to treatment or develop unacceptable side effects from long-term medication.

References

[1] … (Original reference 1)

[2] … (Original reference 2)

[3] … (Original reference 3)

[4] … (Original reference 4)

[5] … (Original reference 5)

[6] … (Original reference 6)

[7] … (Original reference 7)

[8] … (Original reference 8)

(Note: References should be copied from the original article and formatted appropriately)