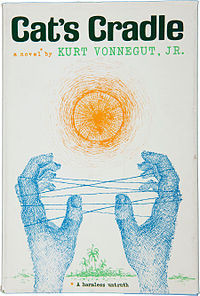

Cat's Cradle First Edition Cover 1963

Cat's Cradle First Edition Cover 1963

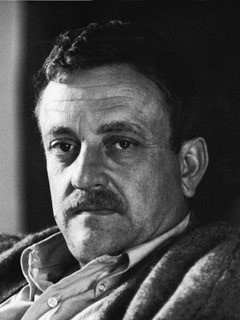

Published in 1963, Cat’s Cradle stands as Kurt Vonnegut’s fourth novel and a towering example of 20th-century satire. Often lauded as a modern Mark Twain, Vonnegut wields his satirical wit to dissect American society and its collective values. While Twain often aimed his sharp observations at more specific societal targets, Vonnegut’s scope is broader, encompassing the absurdities of modern life with a similar zest for exposing human folly. Vonnegut Kurt Cat’s Cradle remains a relevant and darkly humorous exploration of our world.

Kurt Vonnegut in 1963

Kurt Vonnegut in 1963

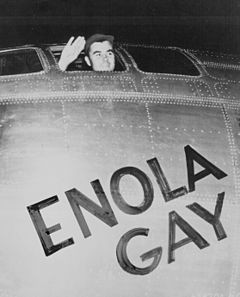

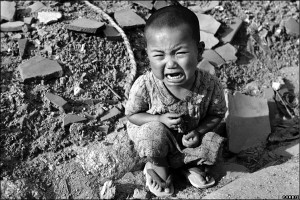

“Call me Jonah,” the narrator declares at the outset of Cat’s Cradle, echoing Melville’s iconic opening in Moby Dick, “Call me Ishmael.” This sets the stage for a narrative driven by an ostensibly detached observer. Jonah embarks on a quest to document the American perspective on the day the atomic bombs fell on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. His focus isn’t the devastation in those cities, but rather the mindset within America at the time, highlighting the chilling ease with which humanity can inflict destruction from a distance.

Paul Tibbets waving from Enola Gay

Paul Tibbets waving from Enola Gay

Vonnegut masterfully underscores the dehumanizing aspect of modern warfare. It’s easier, he suggests, to drop a bomb than to confront the visceral reality of violence. The act of remote destruction allows for detachment, shielding perpetrators from the direct, horrifying consequences of their actions, unlike the brutal intimacy of hand-to-hand combat.

Hiroshima after atomic bombing

Hiroshima after atomic bombing

To understand the American psyche of that era, Jonah seeks out the children of Felix Hoenikker, a fictional co-inventor of the atomic bomb. Hoenikker, long deceased, is survived by his eccentric children: Frank, Angela, and Newt. Newt, the diminutive youngest son, becomes a pivotal figure, revealing a crucial anecdote that encapsulates a central theme in Vonnegut Kurt Cat’s Cradle. When a scientist, reminiscent of Robert Oppenheimer, laments the “sin” they have unleashed upon the world after the atomic bomb test, Hoenikker’s chillingly detached response is simply, “What is sin?”

Robert Oppenheimer at Los Alamos in 1945

Robert Oppenheimer at Los Alamos in 1945

This exchange reveals Hoenikker’s profound detachment from the ethical implications of his scientific contributions. During the very test that birthed the atomic age, Hoenikker was engrossed in playing “cat’s cradle,” a children’s string game – hence the novel’s title. This imagery encapsulates Hoenikker’s, and perhaps humanity’s, dangerous disconnect from the consequences of our creations.

Vonnegut’s own experiences working for General Electric after World War II heavily influenced Cat’s Cradle. Tasked with humanizing GE’s scientists, Vonnegut observed firsthand the potential for scientific innovation to be divorced from ethical considerations. GE’s slogan, “GE–We bring good things to life!” ironically contrasts with the potential for catastrophic misuse of scientific advancements. Hoenikker, in part, mirrors a GE scientist who, according to Vonnegut, jokingly conceived of a substance eerily similar to Ice-9, the world-ending creation in Cat’s Cradle.

Ice-9, initially conceived by Hoenikker as a whimsical intellectual exercise, is a substance that freezes all water it contacts. Its implications are catastrophic and form the core of the novel’s apocalyptic trajectory. Jonah’s journey takes him to the fictional island of San Lorenzo with Angela and Newt Hoenikker. There, he encounters Frank, the eldest Hoenikker sibling, who holds a high-ranking military position under the island’s dictator, Papa Monzano.

As the narrative unfolds, Jonah uncovers the chilling truth: each Hoenikker child possesses a fragment of Ice-9. Vonnegut explores themes of scientific irresponsibility, but also delves into religion through the invented religion of Bokononism on San Lorenzo. Bokononism, with its central tenet that all religions are “foma” (harmless untruths), serves as a satirical commentary on the nature of belief and meaning in a seemingly indifferent universe.

Vonnegut’s own evolving views on religion, ranging from belief to agnosticism to atheism, are reflected in the novel’s ambivalent portrayal of faith. In Cat’s Cradle, God is not malicious, but indifferent, having seemingly abandoned humanity to its own devices. This “cosmic joke,” as Bokononism suggests, is perhaps Vonnegut’s most unsettling proposition: humanity, left to its own devices, is perfectly capable of destroying a world that was once “working just fine.”

The official religion of San Lorenzo is ostensibly Christian, yet Bokononism is secretly practiced by everyone, despite being punishable by “the Hook,” a gruesome execution method ironically reserved for Bokonon himself by the hypocritical Papa Monzano. The “Books of Bokonon,” filled with paradoxical wisdom, are treasured and hand-copied, highlighting the human need for meaning even in the face of absurdity. Bokononism’s core message – “don’t take anything seriously” – underscores the novel’s overarching satirical tone.

Ultimately, Vonnegut Kurt Cat’s Cradle is a cautionary tale. It’s not a condemnation of science, religion, or government in isolation, but rather a darkly humorous and satirical depiction of their potential for misuse and the inherent absurdities of human existence. It reminds us to be wary of our desires and the unintended consequences of our actions.

First encountering Cat’s Cradle in youth, the novel’s humor and rebellious spirit resonated deeply. It served as a reinforcement of anti-establishment sentiments, delivered with a sharp wit that felt intellectually stimulating, echoing Twain’s own evolving perspective on his father’s wisdom. The enduring appeal of Cat’s Cradle is evident in its continued readership, captivating new generations with its timeless satire and thought-provoking themes.

String game resembling Cat's Cradle

String game resembling Cat's Cradle

Cat’s Cradle remains a powerful and darkly funny exploration of humanity’s capacity for both creation and self-destruction, solidifying its place as a key work in Vonnegut’s oeuvre and 20th-century literature. It’s a book that stays with you, prompting reflection long after the final page, prompting us to consider, “So it goes.”